Quakers in the town of Stavanger gave Cleng Peerson an assignment to travel to New York in 1821. They wanted him to explore the conditions for Norwegian immigrants. The assignment was fulfilled in 1825 with the first organized group of emigrants from Norway to the Americas. Cleng Peerson was born in Tysvær, Rogaland county, western Norway, in summer 1783.[1] On April 2, 1807, he married the widow Ane Katrine Sælinger, 34 years older than he. She lived at a cotter’s place under the farm Kindingstad on the island of Finnøy, Rogaland county. Cleng was her fifth husband.

The Quakers in Norway and Stavanger were few, but they felt very much persecuted by the Norwegian Lutheran state church. They longed for the religious freedom in the United States.[2] Peerson himself was not a Quaker but had Quaker sympathies. Between 1821 and 1824 he built up a close relationship with Quaker groups in New York state, especially the Quakers in Farmington in western New York.

A dynamic life with the Quakers in Farmington

Farmington was located about twenty-five miles southeast of Rochester.[3] The Farmington Quakers were the “pioneers of all Quakerism in Western New York, and they were the first white men to bring their families into the vast forest of New York State west of Seneca Lake for the purpose of transforming Seneca’s wilderness hunting ground into a white man’s homeland.”[4] Groups of Quakers had also settled at Macedon and Palmyra, three miles east of Macedon.[5] The Quakers participated actively in the economic boom connected with the building of the Erie Canal.

Cleng Peerson returned to Norway in 1824. He gave his sponsors a positive report, especially about emigration to western New York. The Stavanger Quakers decided in favor of emigration and gave Peerson a new assignment. They sent with him money to locate and buy land for them and do other necessary preparations before their planned arrival in New York in summer 1825.

In fall 1824 Peerson bought land in Western New York

In a letter to friends in Norway, dated December 20, 1824, Peerson reported that he had already executed important parts of his assignment. “It is well known that Cleng Peerson traveled from the Quaker settlement of Farmington, Ontario County, to Geneva,” wrote Richard Canuteson in 1954. During the fall Peerson bought land for the prospective settlers from Joseph Fellows, subagent under Robert Troup, the Pulteney Estate.[6] The Pulteney Estate had for sale vast amounts of land in the region.

The land commissioner in Geneva had received him cordially, wrote Peerson. Fellows had promised him to help the Norwegian group as much as he could on their arrival. “We arrived at an agreement in regard to six pieces of land which I have selected, and this agreement will remain effective for us until next fall.”[7]

The letter from Peerson is crucial for our understanding of the preparations made in the United States before the first group of Norwegian emigrants left Norway in summer 1825. The decisions Peerson made on behalf of the Stavanger Quakers before their arrival defined the subsequent path of dependency. Cleng Peerson bought land only a short distance away from the Erie Canal, the most dynamic economic region in the United States at the time.[8] The region was also a hothouse for religious revivals and new religious sects.

The Restauration left Stavanger on July 4, 1825

Forty-five men, women, and children and a crew of seven emigrated from the city of Stavanger in western Norway on the small sloop Restauration on July 4th. They hoped to find a Canaan’s Land in America. The journey across the Atlantic to New York City marked the beginning of organized emigration from Norway to the United States.

For more than a hundred years historians and novelists have written about the Atlantic crossing and the dramatic events following the arrival of the emigrants in New York City. The Restauration arrived at the port of New York on Sunday morning October 9,1825, after 98 days at sea. “Cleng Peerson met the immigrants at New York, as he had promised,” wrote Theodor Blegen, “and the connections that he had already made in that city stood the party in good stead.”[9]

The Atlantic crossing and the southern route which was chosen, will be covered in articles in these pages later. This story leans heavily on the extensive research Gunleif Seldal has done for many years in primary sources on all aspects connected to the history of the Restauration. In an article presented at the Cleng Peerson Conference in Clifton, Texas, October 2015, Seldal discussed the many different versions told about the Restauration voyage over the years. It was his conclusion then as it is now that much of what had been written was “erroneous, copying has been extensive, myths abound” and many stories were often inconsistent with each other.[10]

How many passengers were on board on arrival in New York?

In his book The First Chapter of Norwegian Immigration, published in 1895, Rasmus B. Anderson presented a list of the passengers on board the “Restauration” . According to Anderson 52 persons were on board.[11] Since 1895 countless researchers have put in tremendous amounts of time trying to verify or refute the names and numbers of emigrants on board. As a good historian Seldal concluded that the sources from 1825 and the first years after can be trusted more than documents written decades later. According to the health certificate from the magistrate in Stavanger in 1825 there were 52 passengers on board. In his report to the Norwegian government the same year, the bishop in Stavanger reported that the Restauration left with 51 passengers, and the US customs officials registered 52 passengers on board. This information is still highly reliable, Seldal emphasizes.[12]

The Restauration and American law

For a vessel of her size, the sloop had too many passengers. The allowed number of passengers was exceeded by 21 persons.[13] The Restauration was confiscated in New York, the captain arrested, and the owners were given a severe fine of $3,150. Luckily the land agent, Joseph Fellows, and Cleng Peerson were present in New York to receive the Norwegian immigrants.

Fellows was an influential man. His network of people in politics and business was large and he got excellent legal help for the Norwegians in relation to the different authorities. A petition was prepared and forwarded to the Secretary of the Treasury. The case of the Restauration went all the way up to President John Quincy Adams. He instructed his administration to prepare a pardon with these words: “Let the penalty and forfeitures be remitted on payment of costs so far as The United States are concerned. J. Q. Adams. November 5, 1825.”[14]

The vessel was sold at a great loss

The sloop was sold for only $400, which was less than a fourth of what had been paid for the ship in Norway. One serious consequence of the low sales price was that the Norwegians had considerably less capital to finance their new Norwegian colony than they had planned. Their lack of capital on American soil came to haunt them immediately.

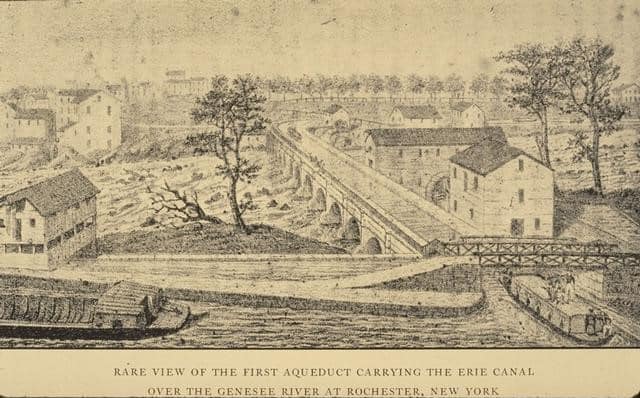

The first Norwegian immigrants boarded a steamship from New York City to Albany, New York, on October 21. The last stage of their travel up the Hudson River and west on the Erie Canal began four days before the official opening of the Erie Canal.[15] The group arrived at Rochester and continued west to Holley, where they arrived in early November. Holley was the harbor on the Erie Canal closest to their land in Orleans County.

Peerson’s land purchase

They settled on the land Joseph Fellows and Cleng Peerson had agreed on in fall 1824. According to long held and stubborn traditions in Norwegian-American immigration history, each adult received a tract of forty acres of land and paid five dollars an acre. According to Rasmus B. Anderson the land was “sold to the Norwegians by Joseph Fellows at five dollars an acre; but as they had no money to pay for it, Mr. Fellows agreed to let them redeem it in ten annual instalments.”[16] The original source of this information was Ole Rynning in 1837.[17]

Almost all later writers have accepted Rynning’s account uncritically. Richard Canuteson is an exception. The Pulteney Estate, the seller of the land, offered the Norwegians the same sales conditions as any other buyer, he argued.[18] The Norwegian emigrants bought their land on credit and would have to pay off all their debts to the Pulteney Estate before they would get title to their land.

Do we know where they settled?

Through research in the Pulteney Papers, Canuteson discovered a map of the land the Norwegians bought. It showed that Cleng Peerson was the owner, “presumptively at least, of four tracts, alone or in partnership with someone else: Lot 15, at the mouth of the creek, 78.52 acres; jointly with Nelson (probably either Nels or Cornelius Nelson Hersdal), the east part of Lot 25, approximately two thirds of the 154.89 acres; the south part of Lot 26, possibly three fifths of the 170.44 acres; and the western part, about two thirds, of Lot 27, 153.70 acres.”[19]

Stangeland and Rossadal shared Lot 37 (97.50 acres) and Hervig and Neilson shared Lot 49 (90.46 acres). George Johnson and Knut Evenson, who came to Kendall in 1831, shared Lot 62 (99.61 acres). Another lot to the south of this one, (96.74 acres) was simply marked “Norwegians”. Between 1825 and 1833, very few among the Norwegian immigrants paid even small amounts on their land.

Joseph Fellows – an immigrant with resources

When Cleng Peerson met Joseph Fellows the first time in fall 1824, he met a lawyer and bachelor his own age. Joseph Fellows Jr. had worked with and for rich and influential people since he was twenty years old. He was born on July 2, 1782, in Redditch, Worcestershire, England. The Fellows family of seven arrived as immigrants in New York in 1795. Joseph was the eldest of the five children, while Lydia, the youngest, was born during the Atlantic crossing. After staying some weeks in New York City, the family continued to Luzerne County, Pennsylvania. The Fellows family settled there and became involved in the coal mining business.

Fourteen-year-old Joseph Fellows Jr. remained in New York. He signed an indenture contract to become a lawyer with the well-known lawyer Isaac L. Kip on June 24, 1796. Joseph was to live in the Kip household and be educated in law. At the end of his indenture, he would become a lawyer. Isaac Lewis Kip was a descendant of the well-known Dutch Kip family, who had lived on Manhattan Island since Holland ruled the colony.[20]

The Pulteney Estate

Fellows met influential men in American politics and business life in the Kip household, such as Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr. He also got to know colonel Robert Troup. When Fellows got his law certificate to practice as a lawyer in 1803, Troup offered him to work together with him as a lawyer for the Pulteney Estate with a yearly salary of $600.

Troup accepted the position as the main agent for the Pulteney Estate in 1801.[21] He was very satisfied with the work of Joseph Fellows during the next years, and in 1810 he promoted Fellows to be the sub-agent at the Geneva office of the Pulteney Estate. Joseph’s salary increased to $2000 per year. In 1824 Troup moved from Albany, the state capital, and back to New York City and Fellows took over the management of Pulteney Estate for the whole area in Western New York. In 1832 he was appointed the main agent for the Pulteney Estate with a yearly salary of $5500 dollar.[22]

Hard work in the forest

The land Peerson had bought, was located in a swampy, forested area with water four feet deep in many places. “The land was thickly overgrown with woods and difficult to clear,” wrote Ole Rynning.[23] The most common items settler pioneers needed to bring with them, wrote Malcolm J. Rohrbough, were money, tools, and seed. To build a shelter for the family had first priority, followed by a log cabin. A lean-to and a cabin would be built from materials at hand, and often at the same time as land was cleared. The land the Norwegians had bought was thickly wooded and it was hard work to clear it. Most of them had emigrated from tree-less landscapes in Norway, and they were not accustomed to forestry work.

Food for the winter was scarce

Their American neighbors knew well how critical the first year was in the life of a new settler. To get the first crop of corn into the ground as soon as possible was crucial. The majority of them had never seen corn before. “Without this gift of the Indian, so easy to plant and so adaptable to frontier conditions, so nourishing and with so many uses, the cycle of life and labor on the early frontier would have been different. From the time of his arrival, the main effort of the early settler was directed to the cultivation of the corn crop.”[24]

The Norwegians arrived at their colony too late in the fall to get a crop in the ground. They had to buy all the food they needed during the first winter. Most of them did not have any cash. The scarcity of nourishing food had its consequences. Many among them experienced extended periods of illness the first years in western New York, and many died. Illnesses they were not accustomed to, flourished in the swamps. Malaria was common in the area, but unknown in western Norway.

Tormod Jensen Madland died in 1826 and his wife Siri in 1829. Aanen Thoresen Brastad (Oyen Thompson) and his youngest daughter Birthe Karine died in Rochester in 1826. Cornelius Nelson Hersdal, the brother-in-law of Cleng Peerson, died in 1833. His widow Kari Pedersdatter was left with seven children aged from a few months to twenty years. Sven Jacobsen Aasen (Swaim Jacobson), who emigrated from Tysvær in 1829 with his wife Johanna Johnsdatter Hervig and three children, died in 1831.

No milk and honey in the forest

The Norwegian immigrants had settled in a dynamic economic region. Very few among them tried to find work beyond their own circle. Some of them had skills needed outside agriculture and got employment. But they had large language problems; hardly any among them spoke many words of English. They sought security by clustering together with their fellow Norwegians.[25]

For several seasons the first Norwegian immigrants in western New York worked hard to grow enough food to feed themselves through a long and cold winter. In letters home to Norway, they were unable to hide their disappointment with their new life in the woods. Very few Norwegians followed in their footsteps.

Notes and acknowledgments

Image credits:

Photos of Restauration: Inger Kari Nerheim

First Erie Canal Aqueduct, Rochester, N.Y., in 1820s: Rochester Image v000163. Courtesy of the City of Rochester, NY.

[1]This intriguing chapter in the history of Norwegian emigration is explored further in Gunnar Nerheim, Norsemen Deep in the Heart of Texas. Norwegian Immigrants, 1845-1900 (College Station, Texas, Texas A&M University Press), pp. 59-63, published March 2024. See also Nils Olav Østrem, «Cleng Peerson – skaparen av den store forteljinga om Amerika», Ætt og heim. Lokalhistorisk årbok for Rogaland 1999 (Stavanger, 2000), pp. 9-10. Andreas Ropeid, «Kristenlivet i åra før 1850», in Stavanger på 1800–tallet (Stavanger: Stabenfeldt Forlag, 1975), pp. 144–147.

[2] Andreas Ropeid, «Kristenlivet i åra før 1850», pp. 144–147.

[3] Blake McKelvey, “The Genesee County Villages in Early Rochester’s History”, Rochester History, 47, no. 1 and 2 (January and April 1985), p. 6.; George S. Conover, ed., History of Ontario County, New York (Syracuse, New York: Lewis Cass Aldridge, 1893), chapter 21.

[4] Alexander M. Stewart, “Sesquicentennial of Farmington, New York 1789 – 1939”, Bulletin of Friend’s Historical Association, 29, no. 1 (Spring 1940), pp. 37-43.

[5] “The Society of Friends in Western New York”, The Canadian Quaker History Newsletter, 37 (July 1985), pp. 6-11.

[6] Richard Canuteson, “A Little More Light on the Kendall Colony”, Norwegian-American Studies, 18 (1954), pp. 82-101.

[7] Cited after Blegen, Theodore C., Norwegian Migration to America, 1825-1860, The Norwegian-american Historical Association, Northfield MN, 1931, p. 39.

[8] Peter L. Bernstein, Wedding of the Waters. The Erie Canal and the Making of a Great Nation, (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2005), p. 272; Ryan Dearinger, The Filth of Progress. Immigrants, Americans, and the Building of Canals and Railroads in the West, (Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2016), p. 31, 37.

[9] Blegen, Norwegian Migration to America, 1825-1860, p. 51.

[10] Gunleif Seldal, “The Sloopers”, paper presented at the Cleng Peerson Conference, Bosque Museum, Clifton, October 2015, p. 1.

[11] Anderson, Rasmus B. The First Chapter of Norwegian Immigration (1821-1840). Its Causes and Results: With an Introduction on the Services Rendered by the Scandinavians to the World and to America. Madison, Wisconsin: privately printed, 1895.

[12] Seldal, “The Sloopers”, p. 16.

[13] A notice published in Den Norske Rigstidende, Oslo, July 25, 1825. Citation from Gunleif Seldal, “The Sloopers”, p. 23.

[14] Theodore C. Blegen, “John Quincy Adams and the Sloop Restauration”, 1940, p. 18.

[15] Ronald E. Shaw, Erie Water West. A History of the Erie Canal 1792-1854 (Lexington, Kentucky, 1966).

[16] Anderson, The First Chapter of Norwegian Immigration, 1895, p 77.

[17] Ole Rynning, Sandfærdig Beretning om Amerika til Oplysning og Nytte for Bonde og Menigmand. Forfattet af En norsk, som kom derover i Juni Maaned 1837 (Christiania, 1839), p. 6.

[18] Canuteson, “A Little More Light”, pp. 82–101. See also FSA Scot, “Sir William Johnstone Pulteney and the Scottish Origins of Western New York”, Crooked Lake Review (Summer 2004); John H. Martin, “The Pulteney Estates in the Genesee Lands”, Crooked Lake Review (Fall 2005); James D. Folts, “The “Alien Proprietorship”. The Pulteney Estate during the Nineteenth Century””, Crooked Lake Review, (Fall 2003).

[19] Canuteson, “A Little More Light”, p. 91.

[20] Isaac L. Kip was born on April 6, 1767, in New York City and died there on January 20, 1837. Jacobus Hendrickson Kip (1631–1690) built a large brick house in 1655 at Kip’s Bay on the East River, Manhattan Island. Frederic E. Kip og Margarita L. Hawley, History of The Kip Family in America (Boston 1928, No. 247), pp. 354–355. During the American War of Independence, a military battle took place there, known as the «Landing at Kip’s Bay». See David Hackett Fisher, Washington’s Crossing (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 102–106.

[21] Alfred Seelye Roe, Rose Neighborhood Sketches, Wayne County, New York; with glimpses of the adjacent towns; Butler, Wolcott, Huron, Sodus, Lyons and Savannah (Worcester, Mass., 1893), pp. XII–XIII. Robert Troup was born in Elizabethtown, New Jersey, on August 19, 1756 and died on January 14, 1832 in New York City. He studied law and shared a room with Alexander Hamilton at King’s College (Columbia University). He served in the American army between 1776 to 1780 and ended up a lieutenant colonel. Congress appointed him Minister of Defence in 1778, and he served as Minister of finance between 1779 and 1780. He worked as a lawyer in New York City between 1784 and 1796. [22] Canuteson, “A Little More Light”, pp. 90-91.

[23] Blegen, “Ole Rynning’s True Account of America”, p. 73.

[24] Malcolm J. Rohrbough, The Trans-Appalachian Frontier. People, Societies and Institutions 1775-1850 (New York: Oxford University Press), 1978, pp. 33-34.

[25] Henry J. Cadbury, “The Norwegian Quakers of 1825”, The Harvard Theological Review, 18, no. 4 (October 1925): 293-319; Anderson, The First Chapter of Norwegian Immigration, 1895, p. 185.

Views: 918