When professor Arthur S. Morton published his book History of Prairie Settlement in 1938, he titled his fifth chapter: “Settlement follows the Railways, 1891-1901.” The railway lines which were completed between 1891 and 1896 came to have a clear direction on the stream of settlers into new areas.[1] The Calgary-Edmonton line was one of these railways. At the end of 1890 the line had been built 94 miles north of Calgary, to the south bank of the Red Deer River. The first train to South Edmonton arrived at eleven in the evening of July 27, 1891. The railway line southwards from Calgary to Fort Macleod was built in 1891 and 1892.

“Between 1891 and 1894 no less than 14 German settlements were established in the country subsidiary to the railway,” Morton wrote; at Hoffnungen west of Leduc, and Rosenthal west of Edmonton in 1891, Wetaskiwin, Rabbit Hills, south of Edmonton, Josephsburg, and Beaver Hills in 1892. “No less than 6 Scandinavian colonies” were established in this area between 1892 and 1896.[2] Swedish colonies were established in 1892 at Edna, 14 miles east of Fort Saskatchewan, New Sweden east of Wetaskiwin and Olds on the railway, followed by Swea at Swan Lake west of Red Deer in 1893. He also mentions an Icelandic colony, but no Norwegian settlement.

Scandinavians found the land in central Alberta attractive

According to the Canadian Census only 304 Norwegians were counted in Alberta in 1901, but by 1911 the number had increased to 5,761. In the 1916 census 6,350 Swedes were living in Alberta and even more Norwegians. The major concentration of people with a Scandinavian background homesteaded along an axis from Wetaskiwin eastward to Camrose.

The settling process followed two main patterns. Individual settlers who came alone or together with relatives or neighbors, was the most common one. This in turn became the beginning of chain migration; others from their place of origin followed later. Another pattern, much more common in Canada than in the United States, was the establishment of group settlements. The group settlement pattern was most common among trans-Atlantic immigrants with a non-British ethnicity and among groups strongly affiliated with fundamentalist churches.

The primary objective of settlers who had grown up in Eastern Canada, mainly in Ontario, was to locate and settle on fertile and productive land. They gave less thought to the ethnic and religious background of their neighbors. But like all newcomers they had to adjust their agricultural skills to the conditions and environment on the western prairies.

Many immigrants from the United States already had experience as dry farmers. They brought with them north not only needed agricultural skills but also more capital than most other settlers in the form of stock, equipment, and cash money. Well established farms in Iowa, Nebraska, Minnesota, or the Dakotas were sold. Old and young moved to Canada to build up much larger farms there than they had ever considered feasible in the United States. Most American immigrants did well on the prairies, but far from all were successful.

Railway sidings and new towns

During the building of the railway from Calgary to Edmonton sidings were planned along the spur. They served new settler districts and became town sites. Every ten miles a siding was put in, and a station and water tank was planned for every twenty miles. These sidings were numbered progressively from Calgary northwards. Siding 14 became Ponoka, siding 15 on the Bear Hills Indian Reserve became Hobbema. Siding 16 north of Calgary was named Wetaskiwin, a name suggested by Father Lacombe and adapted from a Cree word meaning “the hills where peace was made.”[3]

Wetaskiwin

Wetaskiwin had been a buffalo hunting ground used by both Cree and Blackfoot Indians. The river running through the area got the name Battle River, since they at times fought each other over the grounds. The Cree Indians signed a treaty with the government in 1876 and then retreated from the area. Only one white settler lived in the area when the railway company conducted surveys in 1886, increasing to eight in 1890.

Many land-hungry immigrants of Scandinavian descent settled in the Wetaskiwin area, which was characterized by major river valleys and areas with widely separated low hills. It was a transition zone between the short grass prairie to the south and east and the continuous wooded areas to the north and west. The grasslands attracted ranchers as well as farmers.[4]

In 1895 Wetaskiwin was still mainly a railway stop. Because of its topographic advantages, it became a central place for arriving homesteaders in the course of a few months. The terrain east of Ponoka was rough. The terrain also worked against the next siding, Millet. Hobbema was surrounded by the Indian Reserves, while Wetaskiwin was situated in the middle of a broad area of rich soils and open prairie vegetation that spread for miles to the south and east. The northwest end of Wetaskiwin had hills with sandy soil, while the country southeast was very flat and silty.[5]

Wetaskiwin was founded in 1892

There were hardly any buildings in Wetaskiwin in August 1892. In January 1893 the place had four general stores and the largest hotel between Calgary and Edmonton. Wetaskiwin was incorporated as a village in December 1899, became a town on April 5, 1902, and a city in May 1906. The number of inhabitants was 550 in 1901, 2,411 in 1911, 2,061 in 1921, and 2,125 in 1931.

The expansion of homestead settlements in this part of Central Alberta “reveal a pattern of contagious diffusion from the original point of arrival, Wetaskiwin,” wrote William W. Wonders.[6] By the end of 1892 most homestead land within a five-mile radius of Wetaskiwin had been taken. Swedish settlements like New Sweden, Scandia, Malmo, and Water Glen grew up in the area. A group of Swedish immigrants came from Worcester, Massachusetts in 1893.

Norwegian immigrants also settled in this part of central Alberta. Ole M. Olstad and his family was one of the first, coming from Polk County, Minnesota. The family traveled on the Calgary-Edmonton railway, disembarked in Wetaskiwin, and then found their way to the Duhamel settlement. They quickly filed on homesteads for themselves, but also for relatives and friends in the United States. In addition, they purchased CPR land for $3.00 per acre. For a time, the area was known as the “Olstead District”. Several other Norwegian families settled in the area and the name was changed to New Norway around 1895. By 1903 the fledgling community had a school, a general store, and a blacksmith shop. New Norway was located approximately 22 km southwest of Camrose.

Camrose

In 1904 the Canadian Pacific Railroad built a railway line from Wetaskiwin in an easterly direction into Saskatchewan. The new line reduced the role of Wetaskiwin as the main service center in the area. New businesses were opened in many smaller places along the line, but Sparling (later Camrose), some 40 km east of Wetaskiwin, became the new urban center. On May 4, 1905, the railway company chose to name the new town Sparling, in honor of reverend Sparling of Winnipeg, Manitoba.

In May 1904 the Norwegian Ole Bakken established a small store with an upstairs dwelling near Stoney Creek, close to future Sparling. When the railway began running, he moved his shop to Sparling. Within a short time, a harness shop, a hotel, and a “Stopping House” were established. By 1910 so many Norwegians had settled in the area that the Norwegian College Association decided to establish Camrose Lutheran College there, which was later renamed Augustana University College.

In a letter to the Canadian authorities in 1902, recruitment agent Swanson registered that Scandinavians were “coming into Canada from the western states in large numbers, and they are increasing every year.” Most of them purchased Canadian Pacific Railroad land. In 1902 such land was sold for $5 to $10 per acre. Immigrants coming from the United States often chose to buy land from the railroad, while immigrants “coming directly from Sweden would more often take advantage of the Homestead Act.”[7] In spring 1903 so many new settlers arrived that the railroad companies for a time had problems supplying enough railroad boxcars for transport of stock, agricultural equipment, and household goods.

Early Norwegian settlers in Olds, Alberta

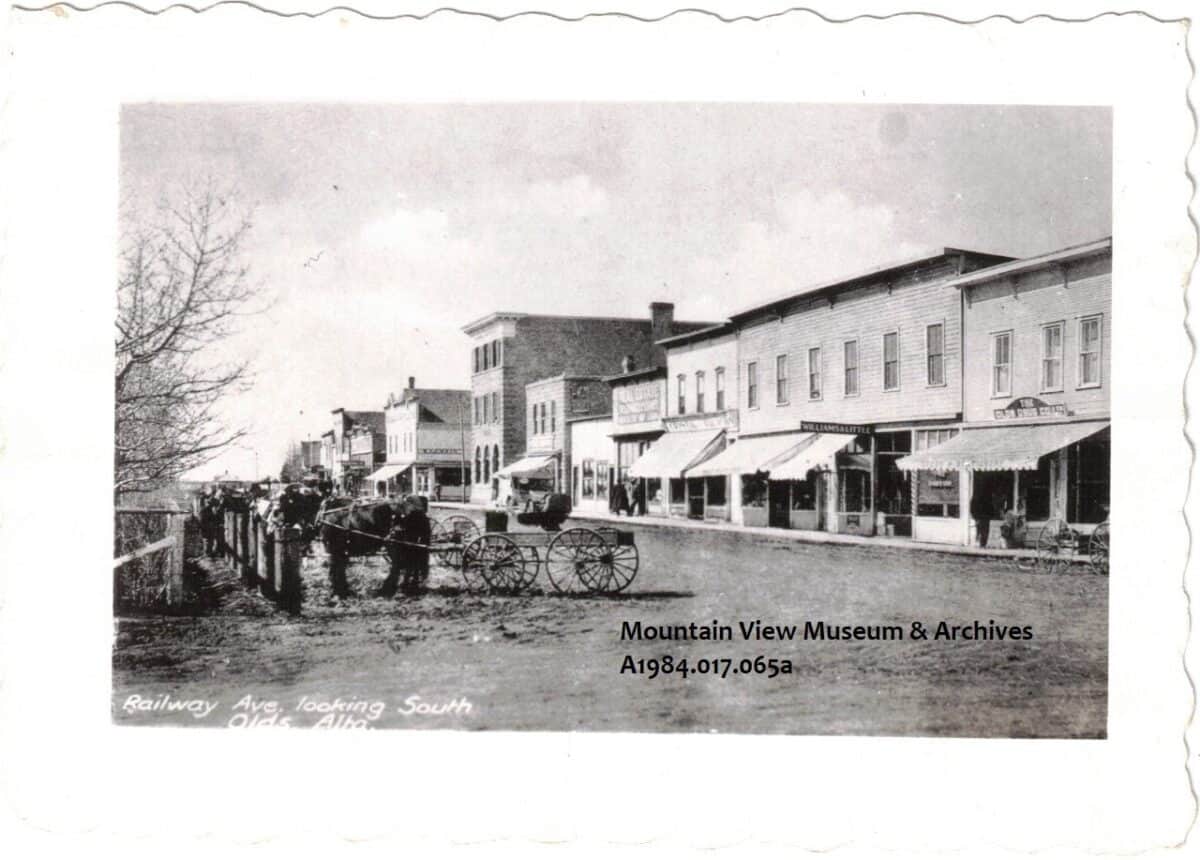

To the south, closer to Calgary, several Norwegians settled in the Olds area. It was located on Siding 6 on the railway line from Calgary to Edmonton and was named Olds in honor of CPR Traffic Manager George Olds. The flow of settlers and businesses increased from 1893. More than a 100 people lived in Olds in 1894. Many of them had come from Schuyler, Nebraska. On one day 90 people arrived at Olds with 20 boxcars full of settler’s stock and equipment.[8]

During the 1890s, almost twice this number continued to come from Nebraska. They hoped to build larger and more prosperous farms than was possible back home. Some of the men, however, gave up after several dry years. At least five families returned within two years of their arrival, convinced that life was better in Nebraska.[9]

A large group of Germans arrived in Alberta around the same time as the immigrants from Nebraska. Close to 300 families settled at Fort Macleod and Olds. A group of Mennonites became early settlers in the Didsbury area under the leadership of Jacob Y. Shantz, who had also been a key figure in the settling of 6,000 Mennonites in Manitoba.[10]

The first large group of Norwegians arrived in Olds in 1902. A majority came from Minnesota (places like Newfolden, Thief River Falls, and the counties of Marshall and Holt). Later many immigrants came directly from Norway, with a concentration of people from Bergen, Oslo and Bardu.[11] The Norwegians at Olds soon earned respect, not least because of their versatile skills as farmers and craftsmen. They made their own buildings and furniture from logs or other material at hand, and the women processed wool from their own sheep all the way from shearing to coloring yarn and finishing garments.

For more than five decades the Eagle Hill district outside Olds was identified with Norwegians. Around 1905 there was only one person who was not Norwegian in that district, and he joked that he had to learn the Norwegian language in self-defence.

Danes and Norwegians

Compared with religious group settlements around Olds, Danes and Norwegians did not stand out to the same degree. Nevertheless, Norwegians continued to use their Norwegian language and taught their children Norwegian, even though they lived in a foreign country. Because of their will to keep up their mother tongue they had a strong tendency to settle close to each other.

Among the first Norwegians to arrive at Olds was Louis Skadsem from Klepp, Jæren, Rogaland County. He came directly from Norway, but he had friends and relatives in Minnesota. He wrote them that the Eagle Hill country around Olds was very similar to the districts they knew from Norway – trees for shelter and fuel, natural springs for fresh water, and abundant wild game. Many among the first Norwegian immigrants who arrived at Olds, lived with the Skadsem family until they could move into their own log houses.[12]

Hans Stroemsmo and his wife, who emigrated from Norway to Minnesota in 1883, followed five other families of Norwegian friends from Minnesota to Olds in 1902. This family and their five children stayed on the Skadsem farm the first weeks after arrival. After 1905 a large group of settlers came directly from Norway and settled in the Bergen district, named after the second largest city in Norway.

Some Danes arrived early around Olds

They settled on productive land north and west in the Samis district. Their land was broken much easier and cheaper than was possible for homesteaders on the more wooded land further west. Most of the early Danish settlers were bachelors. When Jacob Christiansen went back to Denmark in 1906, he persuaded Esper Espersen, Chris Hansson, and Abelgard Jensen, to join him on his return in 1907.

Later Esper Espersen went back several times to Denmark to recruit immigrants.[13] He had a deal with the Dominion government that he would get a free passage to Denmark and back each time he recruited five people to go back with him as settlers on the prairies.

Image credits: Olds street view by courtesy of (C) Mountain View Museum & Archives https://www.oldsmuseum.ca/

[1] Arthur S. Morton, ”History of Prairie Settlement” in W.A. Mackintosh and W. L. G. Joerg (eds.), Canadian Frontiers of Settlement, New York 1938, p. 96.

[2] Morton, op. cit., p. 98.

[3] Siding 16. Wetaskiwin to 1930, published by the Wetaskiwin Alberta – R. C. M. P. Centennial Committee, Wetaskiwin 1975.

[4] William C. Wonders, ”Mot Kanadas Nordväst: Pioneer Settlement by Scandinavians in Central Alberta”, Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography, vol 65 (1983), pp. 129-152,136.

[5] William C. Wonders, ”Mot Kanadas Nordväs”, pp. 136-137.

[6] William C. Wonders, ”Mot Kanadas Nordväst», p. 137.

[7] Viveka K. Janssen, «Swedish Settlement in Alberta, 1890-1930», Swedish American Historical Quarterly, pp. 115-116.

[8] A History of Olds and Area, Olds, Alberta 1980, p. 16.

[9] Bodil J. Jensen, Alberta’s County of Mountain View. A History, published by Mountain View County, Didsbury, Alberta 1983, pp. 13-14.

[10] Bodil J. Jensen, Alberta’s County of Mountain View. A History, p. 14.

[11] A History of Olds and Area, Olds, Alberta 1980, pp. 421, 495.

[12] A History of Olds and Area, p. 16.

[13] A History of Olds and Area, p. 420.

Views: 1137