The first Norwegians in western New York worked hard for several seasons to grow enough food for their families to last through the long and cold winters. Their new home in America was no Canaan’s Land. Could there be a new beginning farther west?

When the ice broke up on Lake Erie and Lake Michigan in 1833, Cleng Peerson headed west to investigate whether the soil was better in the new states of Michigan, Wisconsin and Illinois? Cleng probably chose to travel by canal boat from Kendall west to Buffalo, New York. By the mid-1830s around 3,000 canal boats were operating on the Erie Canal. During the summer season, passengers on Lake Erie between Buffalo and Detroit could travel by steamboat or sailing ship; the latter option was cheaper than the former.

According to some histories on early Norwegian immigration, Peerson walked all the way from western New York, through wetland and beach grasses, sedges, rushes, and shrubs, following the waterfront in Ohio, Indiana and Illinois to Wisconsin and back to Chicago, ending up in La Salle County. As these stories go, he also walked back from La Salle to New York.

West Norwegians and boats

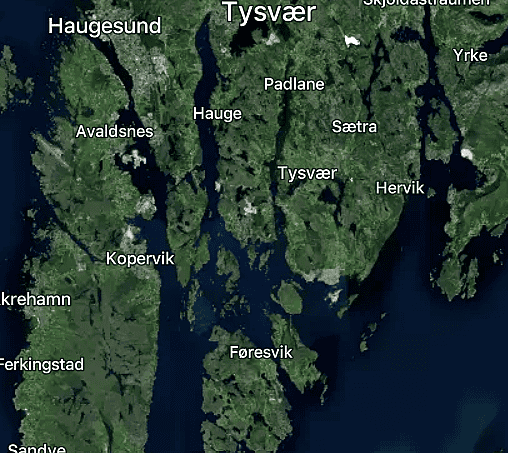

Although Peerson preferred to walk rather than ride a horse throughout his life in America, the reader must not forget that he grew up in Tysvær, Rogaland County. This is a municipality with countless small fjords and coves. Roads were few and far between, and bridges were costly. All Norwegians of his time knew that the most efficient mode of transportation was by boat. The Americans knew it, too. They used the waterways whenever possible.

Cleng used boats when he could, and after his arrival in Detroit he first visited Quakers in Farmington, outside Detroit, Michigan. He knew some of them personally from Farmington, New York. The main road to southern Michigan and Chicago continued south of Farmington. Cleng Peerson knew from Joseph Fellows that both he and members of his family were involved in land speculations in southern Michigan.

During the peak years for land sales, Joseph Fellows and his brother-in-law, Joseph Edward Hill, bought large tracts of land in Berrien County, Michigan.[1] A letter from Hill to Fellows, dated Berrien, October 5, 1837, clearly documents the profitability of their land speculations. Fellows had bought land near Goshen for eight dollars an acre. Because a canal passed through their land, its value had increased to $50 an acre, Hill reported.

Yankee settlers and settlers with Yankee roots in Michigan

Yankees and settlers with Yankee roots were the first white people to settle in Michigan. Southern Michigan soon became known as “Greater New England” or “Yankeeland”. In her book The Yankee West. Community Life on the Michigan Frontier, Susan Gray defined the region as “extending west from New England along roughly longitudinal lines through upstate New York, Ohio’s Western Reserve, the southern half of Michigan’s lower peninsula, northern Indiana and Illinois.”[2]

The main road to Chicago continued south of Farmington. An increasing number of new settlers coming from eastern states in the 1830s used the main road from Detroit to southern Michigan. The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 led to strong migration from the northeastern states to the western frontier. The canal reduced travel time between Buffalo and Detroit by two and a half days, and the trip cost around fifteen dollars.[3] Detroit soon became an important city for new migrants to Michigan.

After the Detroit land office opened in 1818, the number of settlers who arrived in the southern Michigan peninsula and the land around Detroit increased year by year. In 1825, 9,332 acres were registered, which jumped to 217,943 acres in 1831. Sales dropped dramatically during the Black Hawk War and the cholera epidemics in 1832 and 1834. In 1835 sales suddenly leaped to 405,331 acres, and in 1836 to nearly one and a half million acres. The Michigan land boom busted in the wake of the financial panic in 1837. In spite of this, the population of Michigan increased from 28,004 inhabitants in 1830 to 212,267 in 1840, a growth of 658 per cent.[4]

Peerson walked north from the small village of Chicago

From Chicago Peerson first walked north along Lake Michigan on well-used Indian trails between Chicago and Green Bay, Wisconsin. At the mouth of the Milwaukee River, he came to the trading post of Solomon Juneau, who had been trading there since 1818. Juneau was still the leading fur trader on the Milwaukee River when Peerson met him. The land was full of forests, and Juneau told Peerson it would probably never be suitable for farming. Cleng trusted Juneau, turned around and headed back south to Chicago.[5]

Two years later Wisconsin was in the middle of a land boom. Every steamboat arriving at Green Bay in spring 1835 brought more speculators from the east. They were hunting fertile land, mill sites, waterpower rights, and city lots. Homesteaders, interested in building up a farm, followed on the heels of the speculators.[6] In 1836 close to 3,000 inhabitants lived in Milwaukee.

Back in Chicago Peerson walked in a southwesterly direction

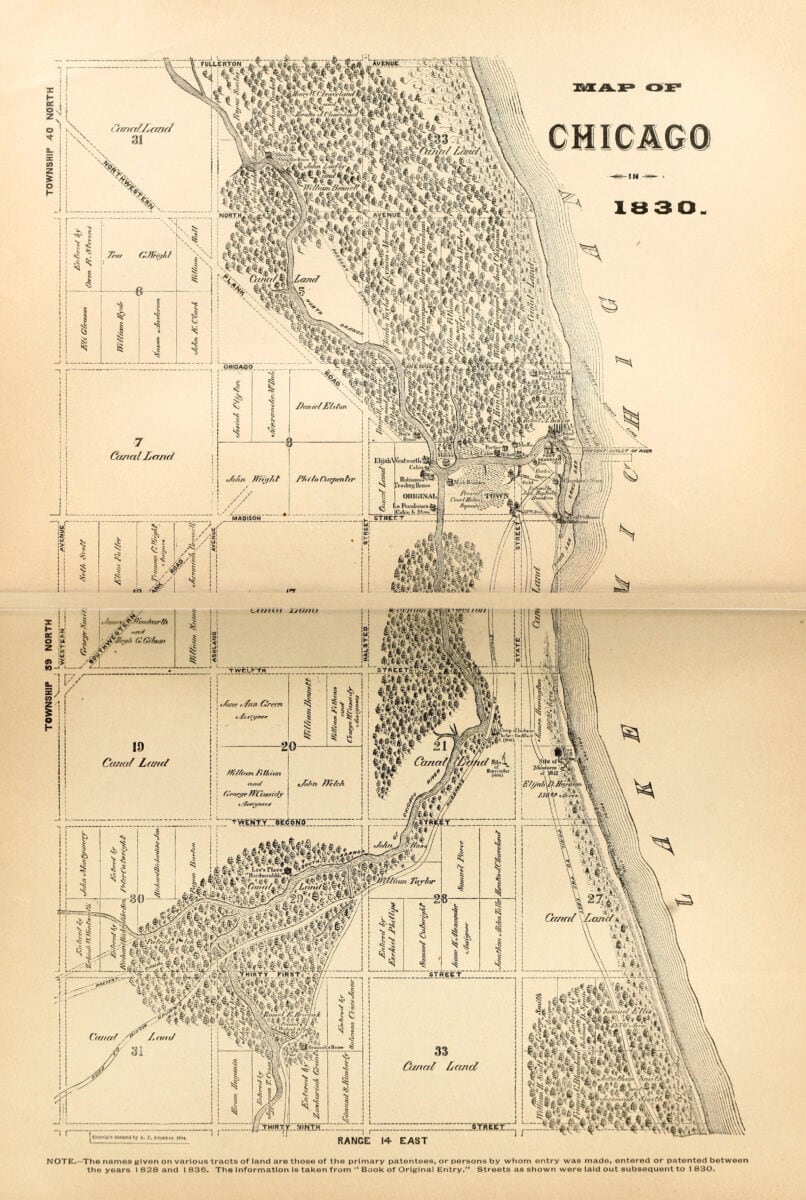

From Chicago Peerson chose to walk in a southwesterly direction. His destination was Ottawa, La Salle County. As early as 1822, the U.S. Congress had passed a resolution granting the state of Illinois a large “land grant” to finance the construction of a new and groundbreaking canal. The canal would connect Lake Michigan and the Great Lakes with the Mississippi River. The first city lots were surveyed and sold in Ottawa in 1830. It was expected that the planned Illinois & Michigan Canal would end there. Because of the war with the Black Hawk Indians in Illinois and Wisconsin in 1832, the sale of property never got off the ground.

After the Black Hawk War was over in spring 1833, speculators and settlers were ready to move into the northern parts of Illinois. However, no political decisions had yet been made on the construction of the canal. Speculators were eager to secure properties on both sides of the planned route of the Illinois and Michigan Canal. Moreover, they expected the price of land along the canal to rise faster than anywhere else in Illinois. Although Peerson was no land speculator, he always had a keen eye for areas that would experience economic growth.

Cleng Peerson founded the Norwegian Fox River settlement

Peerson led the first group of Norwegian immigrants to western New York in the 1820s in the middle of the Erie Canal construction boom. In 1833 he again appeared in the role of trail blazer, wrote Theodore C. Blegen. He “set out on an exploratory journey to the West in search of suitable lands for settlement by the Norwegians”.[7] Blegen admitted that neither he nor other historians had any primary document to prove that “Peerson served as the chosen representative of the Kendall settlers.” But “his glowing reports on conditions in the West found ready acceptance among the New York colonists, for in 1834 six families moved to Illinois and there established the second Norwegian settlement in the United States – the “Fox River Settlement”. ”[8]

Several versions of why Peerson chose to journey west

There are several tales and theories that have been told and repeated about Peerson’s reasons to go west. They all have in common that they are based on secondary sources and indirect evidence. Carlton Qualey assumed it was Peerson’s characteristic feeling of restlessness which probably possessed him, “reinforced by a conviction that western New York was perhaps not the most desirable place in America for Norwegian settlement.”[9] The Norwegians had suffered “great hardship in the last eight years, and besides, the areas of western New York were filling up, and this must have helped to convince him that the opportunities there were far too limited.”

Decades later, Sarah Peterson, Cleng Peerson’s niece and the daughter of the slooper Cornelius Nelson and Cleng’s sister Kari, wrote to Rasmus B. Anderson that her uncle Cleng had “read and heard a great deal about the great country of the west and decided to go and see it for himself. He returned and gave glowing descriptions of the land and people caught emigration fever and moved west. Joseph Fellows also owned land there. The Norwegians were allowed to buy land for $1.25 per acre. There were no dense forests that had to be cut down and burned before plowing and sowing could be done.”[10]

“Cleng’s Dream”. Loved by novelists

Why did Peerson choose the Fox River and La Salle County in Illinois? The later Norwegian American newspaper editor Knud Langeland attended a meeting in Bergen in 1842/1843 for people interested in emigration. Cleng Peerson was present and gave a vivid account of how he had walked for days in a southwesterly direction from Chicago until he came to a ridge overlooking the Fox River valley. “Almost dead of hunger and exhaustion because of his long wandering through the wilderness, he threw himself upon the grass and thanked God who had permitted him to see this wonderland of nature.

Strengthened in soul, he forgot his hunger and sufferings. He thought of Moses when he looked out over the Promised Land from the heights of Nebo, the land that God had promised to his people.”[11] Langeland and most of the audience were prospective settlers. In a footnote Blegen remarked that Peerson probably designed the tale to give Langeland and other listeners a positive image of the opportunities in America?[12]

Numerous accounts of “Cleng Peerson’s dream”

Elmer Baldwin, the author of a comprehensive history of La Salle County, published in 1877, speculated that Cleng might have dreamed his dream while awake? He felt tired and lay down in the shade of a tree and fell asleep. “He had a dream as he slept, in which the wild prairie was converted into a fertile and fruitful land, with corn and wheat of every variety and wonderful fruit. First-class farmhouses and barns were scattered about, housing wealthy and contented families. He awoke refreshed and took the dream with him and told of the place and the dream when he returned to his countrymen in New York, and convinced them to go with him to Illinois.”[13]

Did land speculator Joseph Fellows send Cleng Peerson west?

Fellows had been an active land speculator on his own account for decades. He knew well about the bold canal project between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River. Once construction got underway, migrants would flock to the area and within a few years all the good land would be taken. In the early 1830s, Fellows registered a tendency among farmers who owned Pulteney Land that they sold their land in New York and moved west. He himself began gathering information about properties and bargains in Michigan, Wisconsin and Illinois.

Did Peerson follow the advice of Joseph Fellows?

In his book The Sloopers. Their Ancestry and Posterity, published in 1961, the American Norwegian historian J. Hart Rosdail listed several reasons why Peerson traveled west in 1833. As Qualey had suggested in 1938, he wrote, Peerson might have been sent by the Sloopers to verify rumors of abundant and cheap land, or he might have gone in response to his own well-recognized urges to explore the country. On the other hand, Rosdail suggested, the “Quaker land agent, Joseph Fellows,” may have sent him. “Fellows had considerable knowledge of politics and real estate transactions on the Indian frontier,” Rosdail emphasized.[14] Moreover, he knew that the best land purchases in the future would take place in the Midwest, where he himself was interested in exploiting the opportunities.

Fellows and the political situation for land sales

Joseph Fellows, though no Quaker, had excellent connections with leading politicians and investors and was well acquainted with the political debates on land sales in both Congress and Senate. The election of Andrew Jackson as President of the United States in 1828 represented a political earthquake. Jackson and his supporters worked towards greater democracy for the common man, later known as “Jacksonian Democracy”. They believed all white men had an equal right to vote.

Jackson worked to end what he termed the “monopoly” of government by elites. He and his followers also strongly believed in the concept of manifest destiny, that white Americans should settle the American West and expand their control from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific. Westward lay freedom, eastward lay old Europe. Yeoman farmers should be the ones to settle the West, men who owned and farmed their own land.[15]

The policies introduced by Andrew Jackson would have a negative effect on the profits of the Pulteney Estate and other land projects Fellows was involved in. The best land investments in the future would be in western territories. The planning of the Michigan and Illinois Canal from Chicago to Ottawa in La Salle County had already progressed far. When construction began, land prices on both shores along the canal would increase.

The Fellows family, Cleng Peerson and the Norwegians

Fellows’ relationship with the Norwegians lasted into the 1830s and beyond. There is a strong connection between Joseph Fellows and Cleng Peerson which may have been a factor in some of their decisions and actions in this period. Fellows had known Cleng Peerson since they met in Geneva in 1824. He came to meet the Norwegian group together with Peerson when the Restauration landed in New York in 1825 and used his influence to help them out of their problems.

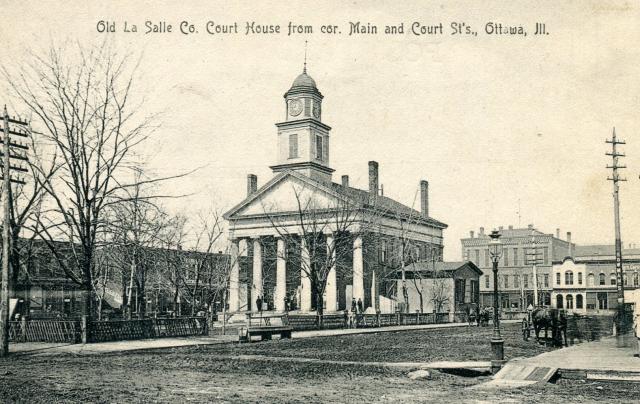

In 1839 the relationship was strengthened through the marriage of Fellows’ nephew and Peerson’s niece. Benjamin Beecher (“Beach”) Fellows, born 1811 in Scranton, Pennsylvania, married Cleng Peerson’s 17-year-old niece, Marthe Karine Hersdal Nelson (1822-1913). She was the daughter of “Slooper” Hersdal and Cleng’s sister Carrie (Kari Pedersdatter). He was the son of Benjamin Fellows, a younger brother of Joseph Fellows. Beach settled on Section 6, Mission, La Salle County, on May 1, 1835. In 1855 he was elected County Treasurer of La Salle County, and the family then moved to Ottawa and lived there the rest of their lives.

Peerson – a man of many gifts

Many sources where we meet Peerson describe him or show through his actions that he was a man with a high degree of selflessness, and with considerable intellectual talent. Over the years he was entrusted with funds, for family and strangers, he was asked to explore possibilities with future consequences for others, to buy land for others, even to go on that long expedition across an ocean. The recent research about his last years in Texas can only substantiate these claims. Even in his old age he walked long distances to help people with legal matters. He moreover bought land on behalf of his sister and her children, and took on several occasions responsibility for finding a good home for orphans when they needed help.

Through assembling these varied and consistent pieces of evidence, we today can draw a clearer picture of a Cleng Peerson: he was a man whom his fellow men could put their trust in. Joseph Fellows would have been able to recognize these traits. He also in great probability perceived Peerson as an intelligent and sharp observer with an uncanny skill to recount what he observed.

A good collaboration

Fellows personally could not be away from his office for months on end. But he was keenly interested in reliable information about landownership in the West. He trusted Cleng Peerson; moreover, Peerson had no financial interests that would compete with his own.

The constantly curious Cleng would find it both challenging and interesting to see with his own eyes where all the immigrants ended up, who now for years had filled up the canal boats on the Erie Canal and gone West. Fellows would have provided Cleng with information on specific places to visit in Michigan, Wisconsin and Illinois. There are strong reasons to support Rosdail’s suggestion that Peerson was not an “advance agent” for fellow Norwegians this time, but for Joseph Fellows.

The first settlers in La Salle County, Illinois, came from the south

The first settlers in Illinois moved north along the rivers into southern Illinois from the hills and mountains of the Carolinas, Virginia, Tennessee, or Kentucky. They had strong ties with New Orleans and the growing steamboat trade on the Mississippi River.[16] The first settlements in Illinois had a clear southern character.

Fox River, on the other hand, begins in Wisconsin and flows into La Salle County in the northeastern corner, between the villages of Northville and Mission. From there, it continues in a southeasterly direction to the Illinois River at Ottawa. The last few miles before the Fox River flowed into the Illinois River, the riverbanks were full of forest, while the prairie ran almost all the way down to the riverbank a little further up. The first homesteaders chose land along the borders with the forest. La Salle became a separate county in the winter of 1830/1831. The first election was held in Ottawa on March 7, 1831.

Unprepared homesteaders

Homesteaders were unprepared when the Black Hawk War broke out. After the Indian chief Black Hawk crossed the Mississippi near Rock Island in spring 1831, the settlers fled their farms. By the spring of 1832, the Indians were on the warpath in earnest. All migration came to a halt. Settlers retreated to larger settlements further south.[17]

The moment an Indian treaty was in place, Joseph Fellows and other land speculators expected western migration to rebound strongly. The Black Hawk War Treaty was signed with the Indians in Chicago on September 26, 1833. The treaty forced the Indians to cede their rights to roughly 1,300,000 acres of land in northern Illinois.

New groups of settlers, mainly from northeastern states, began to arrive in La Salle County in late 1833, the year Cleng Peerson visited the county. Most of them deliberately chose to settle along the Illinois River, where the proposed route for the Michigan and Illinois Canal would be built.

Explosive land sales in Illinois from 1834

Between 1834 and 1835 land sales in Illinois increased by 600 per cent: 354,010 acres were sold in 1834; 2,096,623 acres in 1835. The population of Illinois increased from 157,445 in 1830 to 476,183 in 1840. “Chain migration and group migration ushered many Yankees, other Northerners, and foreigners to Illinois, especially to the northern half – the booming half – stamping that region with unique imprints.”[18] The arrival of the Norwegian immigrants was an insignificant creek in the large westward flowing migration river.

Nevertheless, the arrival of the many foreigners gave a forewarning of the influence the northern line of transportation into Illinois would come to have upon the character of the settlements in these counties. Chicago became the gateway for foreigners into the Midwest prairies.[19]

Paper title to their land

The system of taking land in Illinois was practiced there as it had been done in Kentucky since 1810. The authorities of Kentucky recognized that a settler who had settled on a piece of land was entitled to that piece of land. Possession constituted a legal claim, and such claims were considered valid and could be sold to others. The minimum price was $1.25 per acre.[20] However, neither foreigners nor Yankees got paper title to their land until 1834.

Settlers in La Salle County could not register the land they were already living on until 1835. “Chicago at that time resembled most of all a great swamp.” When La Salle homesteaders travelled to Chicago the last mile was knee-deep in water and the buildings in Chicago looked like log cabins stuck in the mud. “We registered our land and headed home. It was a wild country – full of coyotes, herds of deer, flocks of sandhill cranes, geese and ducks.”[21]

The first Norwegian families in Fox River

The first Norwegian families moved from Western New York to Fox River, Illinois, in 1834. They were the families of Gudmund Hougaas, George Johnson, Jacob Anderson and Andrew (Endre) Dahl as well as Torsten Olson Bjorland, Niels Thoresen Brastad (Nels Thompson) and Cleng Peerson. In spring 1835 came the families of Ole Olsen Hetletvedt (1797-1854) and Daniel (Stensen) Rosdail (1779-1854). Carrie Nelson (Kari Pedersdatter, 1787-1846), the widow of Cornelius Nelson, came with her family in 1836. Her brother Cleng had already bought land on her behalf and that of her seven children.

The first Norwegians settled in the northeastern part of La Salle County, in townships such as Miller and Mission, but some also settled in Adams, Northville, and Serena. Their American neighbors observed that the Norwegians preferred to stay among themselves in their own ethnic colony. They mostly held to the Norwegian language and Norwegian traditions. Only after decades did they show willingness to be integrated into the local community. It was the American school system that taught Norwegian immigrant children to read and write English.[22]

Fellows helped the Norwegians register land in the Chicago Land Office

When the Chicago land office opened in June 1835, Joseph Fellows, the administrator of the Pulteney Estate in Geneva, New York, was present.[23] Fellows knew exactly what each Norwegian settler owed to the Estate back in Western New York and helped them clear their debts so they could move to La Salle County. Over the years, the Norwegians had been cutting down trees, clearing the land, and diverting water from the swampland, etc. From the owner’s point of view, the properties in the area had increased in value due to all the work the Norwegians had done on their homesteads. They got a valuation of their properties, and the Pulteney Estate bought them back, deducting the remaining debt.

The immigrants could now use surplus money to finance their move and journey to Illinois. Fellows played a key role in making it happen this way. On June 15, Jacob Slogvig registered 80 acres and Gudmund Haukaas (Hougaas) 160 acres in Rutland Township. Cleng Peerson registered 80 acres for himself in Mission township on June 17, and 80 acres for his sister Carrie Nelson. On June 25, 1835, Cleng registered another 80 acres of land. In Miller township Gjert Hovland bought 160 acres on June 17; on the same day Thorstein Olson bought 80 acres, and furthermore Nels Thompson (Thorson) 160 acres. Thorstein Olson bought another 80 acres, which he sold to Nels Nelson Hersdal on September 5, but bought another 80 acres on January 16, 1836.[24]

Real estate speculators like Joseph Fellows grabbed most of the land during the sale in 1835. The same month Fellows helped the Norwegians, he registered at least 5,000 acres of land around the Fox River settlement in Illinois in his own name.

The first years in La Salle County, Illinois

During the first two years after their arrival in La Salle County neither American nor Norwegian settlers were able to grow enough food for their families. They had to buy food from settlers who already produced more than they needed. New arrivals without hard cash could work as laborers for others, and most earned enough to provide for themselves and their families. The economic times for farmers in La Salle County were good between the end of the Black Hawk War and 1837, observed Elmer Baldwin. A record number of immigrants came to La Salle in 1836, not least because the work on the canal began on July 4 that year.

Credits and acknowledgements

Images:

Featured image, and small insert: Hand drawn map of the route Peerson traveled to La Salle County and Fox River, published in Gunnar Nerheim’s books on the Norwegian groups’ routes to Texas: (c) Gunnar Nerheim, Fagbokforlaget, Oslo, and Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX.

Map of Tysvær municipality, downloaded Feb.3, 2025, from https://kommunekart.com/klient/tysver/publikum. The municipality collaborates with “© OpenStreetMap, Mapbox, and Mapcarta”.

The unique postcard of Old La Salle County Courthouse in Ottawa, Illinois, built 1839, is used courtesy of Rev. Keith Vincent, courthousehistory.com, who has an impressive collection of American courthouse images.

Image of an “Amerikakiste”- one among the numerous “America trunks”, that traveled a long way before it ended in the Norse District, Bosque County, Texas. The trunk was photographed in Norway Mills by Inger Kari Nerheim, in the Oscar Omensen House, courtesy of the owner, in 2018.

Notes

[1] Orville W. Coolidge, A Twentieth Century History of Berrien County Michigan, The Lewis Publishing Company, Chicago and New York, 1906.

[2] Susan E. Gray, The Yankee West. Community Life on the Michigan Frontier, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1996, p. 1-2; George J. Miller, “Some Geographic Influences in the Settlement of Michigan and in the distribution of its Population”, Bulletin of the American Geographical Society, vol. 45, No. 5, 1913, p. 346.

[3] George N. Fuller, “Settlement of Michigan Territory”, The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, vol. 2, no. 1, June 1915, p. 39.

[4] Miller, “Some Geographic Influences”, p. 321-348, p. 332.

[5] Blegen, Norwegian Migration to America, 1931, p. 61; Nerheim, Norsemen Deep in the Heart of Texas, pp. 63-64.

[6] Mark Wyman, The Wisconsin Frontier, Indiana University Press, Bloomington 1998, p. 158.

[7] Louise Phelps Kellog, “The Story of Wisconsin, 1634 – 1848”, Wisconsin Magazine of History, Vol. 3, No 2, Dec. 1919, p. 190.

[8] Blegen, Norwegian Migration to America, pp. 61-62.

[9] Carlton C. Qualey, Norwegian Settlement in the United States, Northfield, Minnesota, 1938, p. 22.

[10] Anderson, The First Chapter of Norwegian Immigration, 1895.

[11] Citation from Carlton C. Qualey, Norwegian Settlement in the United States, p. 23.

[12] Blegen, Norwegian Migration to America, 1825-1860, p. 61.

[13] Elmer Baldwin, History of La Salle County, Illinois. Its Topography, Botany, Natural History, History of the Mound Builders, Indian Tribes, French Explorations and A Sketch of the Pioneer Settlers of each Town to 1840, Rand McNally & Co, Chicago, 1877, s. 164.

[14] J. Hart Rosdail, The Sloopers, Their Ancestry and Posterity, The Norwegian Slooper Society of America, 1961. Photopress, Inc., Broadview IL., 1961, p. 62.

[15] Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson, Harper & Row Publishers, New York, 1966; John William Ward, Andrew Jackson – Symbol for an Age, Oxford University Press, London, 1953; Anthony F. C. Wallace, The Long, Bitter Trail. Andrew Jackson and the Indians, Hill and Wang, New York, 1993; Steve Inskeep, Jacksonland. President Andrew Jackson, Cherokee Chief John Ross, and a Great American Land Grab, Penguin Books, New York 2015.

[16] Ray A. Billington, “The Frontier in Illinois history”, Journal of the Illinois Historical Society, Spring 1950, vol. 43, No 1, pp. 28-45, p. 31; Elmer Baldwin, History of La Salle County, p. 87.

[17] James E. Davis, Frontier Illinois, University of Indiana Press, Bloomington 1998, p 193-198; Mark Wyman, The Wisconsin Frontier, p. 145-156.

[18] James E. Davis, Frontier Illinois, p. 207, 246.

[19] William Vipond Pooley, The Settlement of Illinois from 1830 to 1850, The Bulletin of the University of Wisconsin History Series, vol. I, 1908, pp. 287-595, p. 385.

[20] Paul W. Gates, “Tenants of the Log Cabin,” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 49, No. 1, June 1962, pp. 3-31; Roy M. Robbins, “Preemption – A Frontier Triumph,” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 18, No. 2, December 1931, pp. 331-349; Paul Wallace Gates, “Southern Investments in Northern Lands Before the Civil War,” The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 5, No. 2, May 1939, pp. 155-185.

[21] Baldwin, History of La Salle County. p. 126.

[22] Baldwin, History of La Salle County. p. 163.

[23] Douglas K. Meyer, Making the Heartland Quilt: A Geographical History of Settlement and Migration in Early-Nineteenth-Century, Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale, Ill. 2000, p. 33.

[24] A. E. Strand (ed.), A History of the Norwegians of Illinois, John Anderson Publishing Company, Chicago ca. 1905, p. 73-75. LaSalle Co. land records, Ottawa, show that Fellows purchased 4,970 acres in townships 34-4, 34-5, and 35-5, 7 sections.

Views: 72