The first organized emigration from Norway to the USA was triggered by the persecution of a small Quaker sect in Stavanger around 1820. The Quakers in Stavanger, western Norway, felt harassed by the state church, by the authorities, and people in the local community.

The Quakers and religious freedom

During the Napoleonic Wars, from 1807 to 1814, the Kingdom of Denmark–Norway was at war with Great Britain. Norwegian seamen were detained in “prison ships” on the south-east coast of England. From time to time, through many years, Quakers visited the Norwegian captives. They were not able to return home to Norway until 1814 and onwards. Some of them began to hold Quaker devotional meetings in private homes in Stavanger and Christiania. Although they were few in number, it was not long before they came into conflict with the authorities.

The State Church did not accept the Quaker community

The authorities grudgingly allowed the Quakers to live in Stavanger and nearby areas, and Stavanger became the headquarters of the Quakers in Norway. But it was a clear condition from the State Church that they should not engage in missionary work. Nevertheless, the Quaker teachings spread to some extent in the coastal communities in the vicinity of Stavanger, in the Ryfylke fjord region, particularly in the municipalities of Tysvær and Skjold, an area with a multitude of small islands and inlets.[1]

State Church pastors claimed that the Quakers were preaching heresy. Their teachings were undermining the official understanding of the gospel. Although the Quakers were a new and small religious community in Norway, they had to accept that there was little religious freedom in the country. Around 1820, Quakers in Stavanger began to wonder whether it might be better to emigrate to the USA? There they would enjoy complete religious freedom.

The Quakers recruited the sympathizer Cleng Peerson

The Quakers knew Cleng Peerson of Finnøy, born in 1783 in Tysvær, north of Stavanger, and that he sympathized with their teachings.[2] In 1821, they hired him to travel to the United States to investigate the conditions for religious freedom and a good livelihood in the state of New York. His friend Knud Olsen Eide from Fogn, Finnøy parish, traveled together with him. The two men went to Gothenburg, Sweden, and made the Atlantic crossing to New York aboard a Swedish ship loaded with iron for export.

Between 1821 and 1824 Cleng Peerson got to know personally Quaker groups in several locations in western New York State. Cleng told Quakers in Farmington, Macedon and Palmyra that he had been sent to scout for a group of Quakers in the town of Stavanger in Norway. They were persecuted by the Norwegian church and authorities, and because of that, they strongly considered emigrating. The Quakers assured Peerson that they would be happy to help their Norwegian brothers and sisters in the Society of Friends in Stavanger, when they arrived in the United States.

Emigration would secure the Norwegian Quakers religious freedom

In the summer of 1824, Peerson returned to Stavanger and presented a conclusive report to his employers. It was his clear opinion that the prospects for religious freedom and livelihood were good in New York. Based on Peerson’s information and further discussions, they decided that a group would emigrate from Stavanger to New York the following summer.

When Peerson traveled back to the USA, his main new assignment was to locate and buy sufficient land for the expected group. During the discussions in Stavanger, Cleng had explained that the Quakers in New York had advised him to build a communal house for the Norwegian immigrants where they could live together the first winter. It was not uncommon for American settlers to live in shared houses during the first winter at a new location. Peerson undertook to build a house for the Norwegian immigrants. The goal was to complete such a house before the winter of 1825/1826.

Among Quakers in Western New York State

On September 20, Cleng Peerson returned to the USA, together with Andreas Stangeland. They crossed the North Sea from Stavanger to England and then continued to New York on a ship from England. After five days in New York City, they continued up the Hudson River on the steamship “William Penn” to Albany, the capital of New York State. The ticket cost them two dollars including food on board. They were going to Farmington, the main center for the western New York Quakers. Cleng had already lived among them for a long time; furthermore, they had promised to help him.

The salt mines at Salina

From Albany and westward to Farmington they traveled partly by boat on the Erie Canal and partly on foot. By autumn 1824 almost 200 km of the Erie Canal was ready for use. On the way from Albany to Troy, they passed the Salina salt mines, which also made a strong impression on them. Smoke from the salt production lay heavily over the landscape. There were a hundred buildings in Salina, and a large population; 1,814 people lived there in 1824. As many as sixty of the buildings were dedicated to salt production.[3] In a letter Cleng Peerson sent to Norway later that winter, dated December 20, 1824, he describes the salt works in Salina in detail.

The Quaker colony Farmington

The Farmington colony was established in the early 1790s by twelve Quakers from Adams in Berkshire County, western Massachusetts. The group had purchased land 25 miles southeast of the town of Rochester, in the northern part of Ontario County, New York State.[4] The property they purchased was part of the vast tract of land Oliver Phelps and Nathanial Gorham had bought from the Indians at Buffalo Creek only a few years earlier, in July 1788. It covered six million acres.

The interest from settlers in buying land was much lower than Phelps and Gorham had imagined. In 1790, Phelps and Gorham sold the land to the speculator Robert Morris for 200,000 dollars. Robert Morris was widely known for buying and selling property on a large scale. Already two years later he sold parts of the properties for 360,000 dollars to a group of British investors led by Sir William Pulteney. After Sir William Pulteney died in 1805, the name was changed to Pulteney Estates.

The new Quaker community in Farmington erected a gristmill as early as in 1793, and a sawmill in 1795. The settlers also soon began to produce potash, used for centuries to make soap and to bleach textiles. A Quaker house, a meeting place for Quakers, was built in 1796. The Quakers of Farmington were “the pioneers of all Quakerism in Western New York.”[5]

Some Quakers from Adams, Massachusetts, also settled in Macedon, 7.5 miles north of Farmington, and in Palmyra, three miles east of Macedon. Around 1820, there were approximately 75 Quaker families living in Farmington, Macedon and Palmyra.[6] Cleng Peerson knew personally Quakers in all three locations.

Land for the Norwegian emigrants

When the state of New York decided to build an inland canal from the Hudson River to Lake Erie in 1817, the construction work led to boom times. A stream of settlers came to western New York, where the Indians still lived. Most of the whites had grown up in New England and in the states of New York and Pennsylvania. A number of Irish immigrants working on the canal also settled in the area after its opening.[7]

Peerson’s most important task after his return to Farmington was to buy land for the Norwegian group that planned to arrive the following summer. The Quakers in Farmington were active and capable participants in a bustling community. To aid the newcomers, they built on their own experience as early settlers in the region. They recommended that Cleng buy land from the largest landowner in the area, Pulteney Estates. This company had its own agent in the town of Geneva. It was located at the north end of Lake Geneva, about 25 miles east of Farmington.[8]

His friends advised him to go there and negotiate with the lawyer Joseph Fellows. In his letter to Norway in December 1824, Peerson wrote that the land agent Fellows had received him with great kindness. “We agreed on a deal for six pieces of land which I selected, and this deal is binding until next fall.”[9] A communal house was being built on the land he had selected, “12 feet long and 10 feet wide”. This building would be their home during the first winter.

Organizing the first Norwegian emigration

On his way from Geneva, Peerson stopped in the rapidly growing city of Rochester. There he bought an iron stove for ten dollars, which also included pots and pans. He had previously bought a cow for ten dollars and some sheep. Quakers in Macedon had offered to take care of the family of Peerson’s sister Kari and others until the log house with enough room had been built. The moment the full length of the Erie Canal came into use in 1825, Peerson wrote, real estate prices in this region would rise.

The letter Peerson wrote in December 1824 is practical and shows the meticulous planning that was being done on behalf of the Norwegian group, by Peerson and his American friends. Their optimism is easy to see. The letter is crucial to our understanding of what happened before the emigrants left Norway in 1825. The decisions made on their behalf before they arrived in New York influenced a number of decisions made in the fall and winter of 1825. However, the 1824 letter did not become public knowledge until 1924, one hundred years after it was written.[10]

Quakers as well as other emigrants

The first organized emigration from Norway to the USA was triggered by the plight of the small Quaker groups in western Norway. However, far from all the emigrants on board the small vessel that arrived in the harbor of New York City were members of the Quaker sect. Their reasons to emigrate were certainly as diverse as the reasons of those who came after them, and the people who emigrate today. Where they went from this phase, continues to surprise. For instance, Cleng Peerson, the pathfinder, ended up in Texas, his niece in Utah. Many died the first years, the initital optimism notwithstanding. The study of their motives, their planning, their fortunes, the changing world they plunged into, open our minds to understand the always changing processes of human society.

Credits

Image of prison ship: Painting of prison hulks and other ships, River Thames, England, circa 1814, unknown artist. This is a cropped and digitally repaired version of an image in the State Library of New South Wales, and now only available at the Wikikedia site, see the following link. Originally created: 1814, public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Prison_ships#/media/File:Painting_of_prison_hulks_and_other_ships,_River_Thames,_England,_circa_1814.jpg

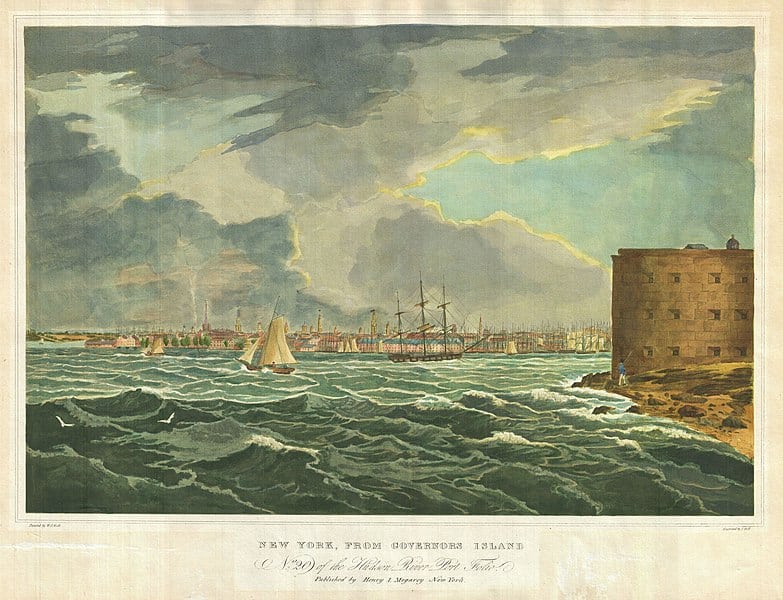

Image of New York Harbor: This is plate no. 20 from William G. Wall, and Henry L. Megarey’s important 1825 Hudson River Port Folio. It is considered to be the first and finest set of views of the Hudson River ever published. The portfolio was based upon a series of watercolors by the Dublin-born artist William Guy Wall. The New York publisher Henry Megarey hired John Hill to create a series of aquatints based upon Wall’s work. http://www.geographicus.com/mm5/cartographers/ . This file was provided to Wikimedia Commons by Geographicus Rare Antique Maps, as part of a cooperation project. It is open to use in the Public Domain. File:1825 Wall and Hill View of New York City from the Hudson River Port Folio – Geographicus – NewYorkGovernorsIsland-hudsonriver-1825.jpg. Created: 31 December 1824. Uploaded to Wikimedia Commons 25 March 2011 and to clengpeerson.no 16.01.2025.

Notes

[1] Andreas Ropeid, “Kristenlivet i åra før 1850”, in Stavanger på 1800-tallet, Stabenfeldt Forlag, Stavanger, 1975, pp. 144-147.

[2] This article is based on Gunnar Nerheim, I hjertet av Texas. Den ukjente historien om Cleng Peerson og norske immigranter i Texas, Fagbokforlaget, Bergen 2020, p.33-46. See also Nils Olav Østrem, “Cleng Peerson – skaparen av den store forteljinga om Amerika”, Ætt og heim. Local history yearbook for Rogaland 1999, Stavanger, 2000.

[3] Dwight. H. Bruce (ed.), Onondaga’s Centennial, vol. 2, Boston History Company, Boston 1896, pp. 933-961.

[4] Blake McKelvey, “The Genesee County Villages in Early Rochester’s History”, Rochester History, Vol. XLVII, January and April 1985, Nos. 1 and 2, p. 6.

[5] Alexander M. Stewart, “Sesquicentennial of Farmington, New York 1789 – 1939”, Bulletin of Friends’ Historical Association, Vol. 29, No. 1, Spring 1940, pp. 37-43.

[6] “The Society of Friends in Western New York”, The Canadian Quaker History Newsletter, no. 37, July 1985, pp. 6-11.

[7] Ryan Dearinger, The Filth of Progress. Immigrants, Americans, and the Building of Canals and Railroads in the West, University of California Press, Oakland 2016, pp. 31, 37.

[8] Richard Canuteson, “A Little More Light on the Kendall Colony”, Norwegian American Studies, vol. 18, 1954, pp. 82-101. The investors in the Pulteney Association were a group of men led by Sir William Pulteney, 5th Baronet (1729-1805). Jeffrey M. Johnstone, FSA Scot, “Sir William Johnstone Pulteney and the Scottish Origins of Western New York”, Crooked Lake Review, Summer 2004; John H. Martin, “The Pulteney Estates in the Genesee Lands”, Crooked Lake Review, Fall 2005; see also James D. Folts, “The ‘Alien Proprietorship’. The Pulteney Estate during the Nineteenth Century”, Crooked Lake Review, Fall 2003.

[9] Quoted from Theodore C. Blegen, Norwegian Migration to America, 1825-1860, Northfield, Minnesota 1931, p. 39.

[10] Blegen discussed the provenance of the letter in detail in an appendix to his book Norwegian Migration to America, 1825 – 1860, p. 382.

Views: 27