Two Grande brothers from Trondheim, the middle of Norway, in 1866 set out on a long and winding journey to the United States. They crossed fjords and oceans, followed rivers, roads and trails over plains, valleys and mountain ranges before they ended up in the grassy Musselshell Valley, Montana, in 1878. The journey was not one of a kind, since many travelers followed similar routes in similar ways in the years before and after. It can generally be seen as a model of an emigrant route in the second half of the 19th century. The story of their lives gives examples of very many aspects of the emigrant’s life.

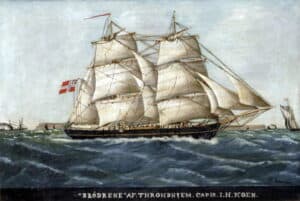

A safe ocean crossing was obviously a crucial part of the journey to America from all European countries. In this case the bark “Nicanor,” with a gross tonnage of 438 and built in Skellefteå, Sweden in 1857, left Trondheim on May 25, 1866. It was to sail to Quebec in Canada with five cabin passengers and 233 emigrants in steerage.

Anton and Martin T. Grande

Among the passengers on board were Anton Grande, born 1843, and Martin T. Grande, born on August 17, 1844. The brothers had grown up on the farm “Grande Øvre,” Upper Grande, at Verran, on the north side of the Trondheimsfjord, and were the sons of Tørris Pedersen and Christianna Jeppesdatter. They had four older brothers. At the time of the Norwegian Census in 1865, the farm had been transferred from the father to the oldest son Ole Tørrisen, 41 years old, and his wife Nicolina Paulsdatter. Moreover, two brothers were away at sea.

The year before they left, in the 1865 Census, Anton was registered employed as a “dreng” or agricultural laborer on the farm “Wennes Søndre”. Martin, meanwhile, worked as “dreng” for the farmer Peter L. Paulsen on “Grande Nedre”, Lower Grande, which was a rather large farm by Norwegian standards. The farmer in this case employed two “drenger” and three “tjenestepiker”, maids. In addition he owned three horses, eleven cows, twenty-six sheep and three hogs.[1]

The future was not too bright for two younger brothers in the farming community where they grew up. If they were lucky, they could marry a girl who already owned a farm or was likely to inherit one. If they were unlucky, they might end up as “husmenn” or cotters under a larger farm, essentially agricultural workers.

Emigration from the Trøndelag region

Only modest emigration from Trøndelag region began before the outbreak of the Civil War. Norwegian sailing ships participated in the Quebec timber trade but had to cross the Atlantic from Norway to Quebec in ballast. To fill their holds on the voyage west, shipowners from southern and western Norway found it worthwhile to sail north to Trondheim first and fill their holds with emigrants, and in this way created a new emigrant route. Every year between 1858 and 1862, the brig “Brødrene” left Trondheim for Quebec with emigrants on board. In 1865 the bark “Bergen” left Trondheim on May 14, and arrived in Quebec on July 3.

The real breakthrough for emigration from Trondheim came in 1866.[2] Between April and June five sailing ships left Trondheim for Quebec. “Victor” was the first. She left Trondheim on April 25, and arrived in Quebec on June 9, followed by the bark “Neptunus” on May 5, which arrived in Quebec on June 9. The bark “Nicanor” set sail on May 25, and arrived on July 10, followed by the bark “Vidfarne” on May 26, arriving on July 18. The last ship to leave Trondheim with emigrants that season was the bark “Telegraph”. She left on June 2, and arrived in Quebec on July 22.

The “Nicanor” crossing

Because of an emigrant letter from one of the passengers, we know more than usual about the “Nicanor”-crossing to Quebec and the further travel to the final destination. Most of the passengers on board intended to join relatives and friends in Fillmore and Houston counties in southeastern Minnesota.

The “Nicanor” left Trondheim at 6 p.m. on May 25. The steamship “Finnmarken” towed the bark about six miles out on the Trondheimsfjord. In due time, the ship set sail, and a mild north-east wind brought the ship further out into the big ocean. Most of the emigrants had never been at sea before and many became seasick, including the letter-writer Erland Taraldsen Tomasrud, his wife, his brother and sister-in-law. Everything went well until June 21, when a young man aged 21 died from a brain infection. It made a big impression on the passengers when the man was buried in the deep of the ocean, around 50 miles east of Newfoundland. “The captain held a beautiful speech, and laid sand on the body before he was lowered into the water.”[3]

The first glimpse of the American continent

The passengers saw the Canadian coast for the first time on July 3. When the “Nicanor” reached the quarantine station at Grosse de Isle below Quebec, two of the passengers on board were sick. One was diagnosed as debilitated while the other suffered from fever. The ship was detained for a day and arrived in Quebec on July 10. The emigrants hired a person skilled in Norwegian and English as their guide in Quebec, and from Quebec to Chicago.

From Chicago the majority among the emigrants continued to Brownsville and Spring Grove, Houston County, Minnesota. The Grande brothers had no special preference about where they wanted to settle. Accordingly, they followed the main group to Houston County in south-eastern Minnesota, on the border with Iowa. To the east was the Mississippi River and the state of Wisconsin, and to the west lay Fillmore County.

Dense Norwegian settlements in Minnesota

Spring Grove township in the southwestern corner of Houston County was a central part of tightly knit Norwegian settlements extending from western Houston County to the western part of Fillmore County. Because of the density of Norwegians in Fillmore and Houston counties, the Norwegian language and Norwegian customs remained vibrant for a long time in this area.

If Fox River, Illinois, was the Norwegian mother colony before the Civil War, Fillmore and Houston counties came to play much the same role during the first decade after the war. Hundreds and thousands of Norwegian immigrants lived for a short time in these counties before moving further west into Minnesota, and to the Dakota and Montana territories.

Spring Grove, Minnesota

Norwegian families and single men had settled in Spring Grove as early as 1852. Most of them moved from older Norwegian settlements in southern Wisconsin – Koshkonong, Muskego, and Rock Prairie. A few also came from recently begun settlements in north-eastern Iowa. “They did not go to Spring Grove Township directly from Norway but were part of the westward movement of the American population, which was at this time pushing north-westward from the southern tip of Lake Michigan and which picked up immigrants from Norway on older frontiers and sent them out to the newer frontiers along with the native Americans.”[4] Norwegian immigrants found it important to settle among fellow Norwegians who spoke their language and shared their Lutheran faith. Neighbors were more important than to settle on the best soil available.

At the time of the US census in 1860, Spring Grove township had a total population of 545 people (98 families) and 480 of them were Norwegians (86 families). All the Norwegians were engaged in farming. After the Civil War, a flow of immigrants came directly from Norway to Spring Grove. Of the 231 families (1,325 persons) living in Spring Grove Township in 1870, 196 families (1,135 persons) were Norwegian. However, by 1870 all the best land had been taken and land prices had increased considerably.

The “Nicanor” group arrived at Spring Grove

The “Nicanor” group arrived at Spring Grove in 1866. The newcomers were soon told that it might not be easy to find work in the County nor to buy cheap land. The Grande brothers had no money to invest. If they traveled further west, they were told, they could get harvest work in the wheat fields. A farmer hired them at a salary of 0.75 to 1.00 dollar per day. When the time came for them to get paid, however, the farmer said he had no cash. He offered them two head of cattle as their salary. They accepted the deal and later sold the cattle.

Agricultural laborers often had problems finding jobs during the winter. The Grande brothers found work in the Michigan woods, where they they picked up stories about the Norwegian sawmill entrepreneur Holte, who operated a large sawmill company as far west as Helena, Montana. Holte usually hired Norwegians in his sawmills. In spring 1867, Anton Grande traveled to Helena hoping to get a job, while his younger brother Martin went to Wyoming. There he hired on as a worker in the coal fields in the new coal town Carbon.

In the coal mines at Carbon, Wyoming

The Union Pacific Railroad needed to burn large amounts of coal to produce steam to power the locomotives. Coal accordingly became an important resource in the West. Carbon was the first coal town in Wyoming. It had rich coal reserves and was located about halfway between Laramie and Rawlins.[5] In November 1867, the Union Pacific railroad reached Cheyenne and crossed the border into Utah in early 1869.

Visitors to Carbon during the first years found a scattered and disorganized place full of dugouts and log cabins. As a result, infectious diseases like typhoid, diphtheria, and cholera were well known in the place. Many Finnish and Scandinavians immigrants worked in the coal mines.

Anton soon returned from Montana to the Michigan lumber camps.[6] In 1872 Martin left Wyoming by stagecoach to Helena, Montana, via Salt Lake City. The first couple of years in Montana he only found temporary work, for example to cut cord wood for the military at Camp Baker near White Sulphur Springs in Meagher County. The fort had been built in 1869 in response to demands from miners at Diamond Gulch. They had argued that the political authorities should establish a fort in the vicinity to protect them against Indian attacks. The fort contained sleeping quarters for a hundred men, officer’s quarters, a hospital, a laundry, and a post office. The name changed to Fort Logan in 1879.[7]

Hunting with Peter Jackson from Trøndelag

For a while Martin Grande cut cord wood for the railroad at Sun River. During his time there he met a fellow Norwegian, who had emigrated from the same region in Norway. Peter Jackson supplied the railroad camp with wild game meat. He was born on October 21, 1846, and emigrated from Trondheim through Quebec to Wisconsin in 1869. Jackson worked for a while at a sawmill at Menominee, one of the main suppliers of lumber to the building trade in Chicago.

In 1871, Jackson chose to go west and traveled on the Union Pacific to Ogden, Utah. In Montana the two Norwegians, twenty-six and twenty-eight years old, even from the same region, formed a joint venture with the purpose of hunting elk along the forks of the Musselshell River. Game was plentiful: Martin once witnessed a buffalo herd so large that it took the animals three to four days to file through the pass near the headwaters of the Musselshell.[8] One spring the two men delivered four hundred elk hides at a trading post on the Missouri River. On average they killed more than two elks per day during the six winter months. After the hunting season was over, Jackson and Grande divided eight hundred dollars between them.

Peter Jackson left the Musselshell area

In 1876 Jackson wanted to hunt buffalo in the Yellowstone River country and settled at the mouth of Little Porcupine Creek where it flowed into the Yellowstone River, a few miles west of Forsyth. Jackson married Mary Price on April 11, 1883, in Forsyth, Rosebud County. This was in fact the first wedding between two white people ever to take place in Forsyth. A special Northern Pacific railroad car brought a band from Fort Keogh to play at the wedding. The newlyweds settled on the Jackson ranch, and over the years they became the parents of six children.

Big game hunting was more tiring than mining

The Smith Brothers, owners of a gold mine at Thompson Gulch west of White Sulphur Springs in Meagher County, offered Grande work as a miner in the summer combined with miscellaneous work on their ranch on Willow Creek, east of White Sulphur Springs, in the winter.

The Smith brothers were among the first sheep ranchers in Meagher County. John M. Smith was born in Fairfield, Ohio, on October 6, 1833. His ten year younger brother William A. Smith was born in Williams County, Ohio, in 1843. At the age of twenty-one, John moved west to California by way of Panama and worked as a miner in California for several years.

When the news of the discoveries in Virginia City, Nevada, reached California in 1860, John Smith moved to Nevada. He prospected around Gold Hill and Comstock for a year. The war with the Ute Indians made further prospecting risky and he returned to California. In 1863 he sailed to Portland, Oregon, and joined a group of men eager to try their luck at Placerville, Idaho. By this time, his brother had joined him. The two brothers worked well together until William died at White Sulphur Springs, Meagher County, Montana, on February 12, 1897.

The Smith Ranch was located four miles west of Martinsdale

The Smith brothers tried their luck at Last Chance Gulch in 1866, but in the fall, they worked on a threshing team in the Gallatin Valley. In 1867, they chose to farm in the valley, but grasshoppers ruined their crop. In 1868 they began prospecting at Thompson Gulch, eighteen miles west of White Sulphur Springs. Their mining was a success the first year, but the second year proved disappointing.

They began ranching in the Musselshell Valley in winter 1871/72 and built more permanent living quarters there in 1873. The two brothers traveled south to Boise, Idaho, in 1873. They bought one hundred head of Oregon Short Horns for eight dollars per head from John Haley, an influential stockman in Boise.[9] The brothers learned that Haley also had a large flock of sheep. Two years later the Smith Brothers entered the sheep business.

They returned to John Haley and bought nine hundred head of Merino ewes for 1.50 dollars a head. It took the brothers most of the summer to move the flock north to the Musselshell Valley, and later to Willow Creek, four miles east of White Sulphur Springs. This was the first flock of sheep that ever grazed along the Musselshell River.[10] By 1902 John Smith owned 43,000 head of sheep and raised 20,000 head of lambs.

Martin Grande as partner with the Smith Brothers

Martin Grande left the Smith Brothers’ employ and began working as a sheep herder for Potter and Ford on their place south of White Sulphur Springs in 1876. Grande had built up considerable trust with the Smith Brothers, however, and in spring 1877, they offered Grande a partnership in their sheep business.

After eleven years as an itinerant worker in the in the United States, Martin T. Grande finally got his big chance to succeed or fail. After they signed the partnership, William Smith and Martin Grande traveled to Helena to buy a wagon and supplies. They returned to the Musselshell River and then set the course for Boise, Idaho, where they bought 2,000 head of yearling Merino ewes from John Haley for $ 2.50 per head. The two men drove the flock north to the Smith Ranch on the Musselshell River by way of Horse Prairie, Bannack City and Radersburg. The whole flock was shipped across the Missouri River by ferry at Toston and arrived in the Musselshell Valley in August 1877.[11]

The trip from Boise to Meagher County took place during the summer of the Nez Perce Indian uprising. At Bannack, on their way to Boise, Smith and Grande were warned that it would be dangerous to continue to Boise. They ignored the advice and came to no harm.

The sheep wintered on the Smith Ranch near Martinsdale

Martin T. Grande and John and William Smith owned the band of 2,000 ewes jointly. About fifteen hundred lambs were born in spring 1878. “The sheep were shorn and the fleeces piled up as no bags had been secured. Wool prices were low and there were no buyers closer than Helena.”[12] Martin Grande got the job of freighting the wool to Helena with big wagons powered by ox teams. But when he arrived in Helena, the buyers had already left. To sell the fleeces and ship them to woolen mills in Boston, Grande ended up driving east all the way through the Musselshell Valley, through Judith Gap and to Carroll on the Missouri River, more than 250 miles.

The Grande Ranch on Comb Creek

The partnership between the Smith Brothers and Grande ended in spring 1879. Grande left with a third of the flock and located on a place he had chosen at Comb Creek, a few miles west of the Smith ranch on the Musselshell River. Grande had discovered the place during his time as a big game hunter. The place had a year-round stream close to Comb Butte in the vicinity of Lennep. Timbered areas close by supplied the homestead with wood and logs for housebuilding and fuel.

To the north lay protecting mountains, to the west, south and east lay large and open grazing areas. Down-slope winter winds helped clear the range of snow for the livestock. His brother Anton was trying his luck in the Black Hills gold rush, but soon joined Martin when he established his new sheep ranch in Meagher County. The two brothers formed a partnership in the ranching and sheep business under the name of Grande Brothers.

The first home was a two-story log house

The Grande brothers built a two-story log house a mile north of Comb Butte. A row of small log buildings provided space and shelter for horses, cows, and chickens. Some years later they raised a much larger and more comfortable frame house half a mile to the north.

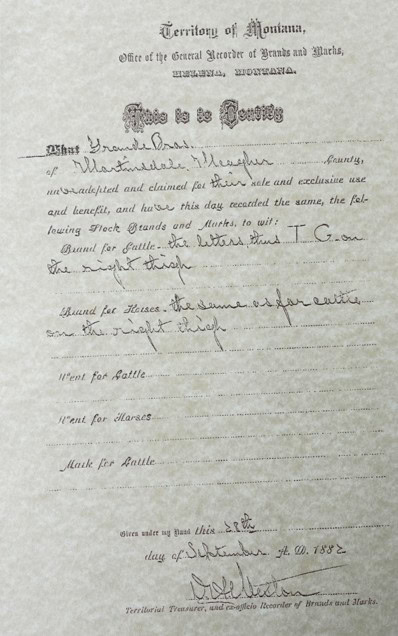

The number of ranch buildings were steadily growing, and up on Little Cottonwood Creek Grande installed a steam engine and a sawmill. The fir timber was also close at hand. By 1883 the Grande brothers had built up their flock to 4,800 sheep. Around this time the brothers also began building up a small herd of cattle. They registered “TG” as their livestock brand in Helena.

Grande financed his part of the partnership with the Smith Brothers with borrowed money. After that, he never again loaned money to build up his flock. Through careful selection of bucks, he bred one of the finest flocks of sheep in the Musselshell valley.[13]

The Grande partnership suffered a big blow in August 1880. Anton was seriously injured by a trail wagon on a street in Helena. He survived the accident but never quite recovered. When Anton Grande died in 1897, the partnership was dissolved. At that time, the Grande ranch had 12,000 head of sheep.

Martin Grande had built up one of the largest sheep ranches in Meagher County. Over the years he hired many Norwegian immigrants as sheep herders. Not all, but some of them, saved money to build their own sheep ranches.

No other settlers along the Musselshell South Fork

There were no other white settlers west of the forks when the Smith and Grande brothers settled along the Musselshell South Fork. The country was all open range and used as common pasture. Some cattle ranchers from the Smith River area near White Sulphur Springs used to trail cattle to the Musselshell for wintering but returned them to the Smith River Valley in summer. At first neither the Grande brothers nor the Smith brothers filed for homesteads, but after some years they began to register parts of their land.

Credits

Images:

From Spring Grove: The Ellingson glass plate collection, courtesy of Giants of the Earth Heritage Center, giantsoftheearth.org. Original photo downloaded from their Facebook gallery site www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.10155109959865937.1073741912.121961225936&type=1&l=02dc504814 and slightly edited.

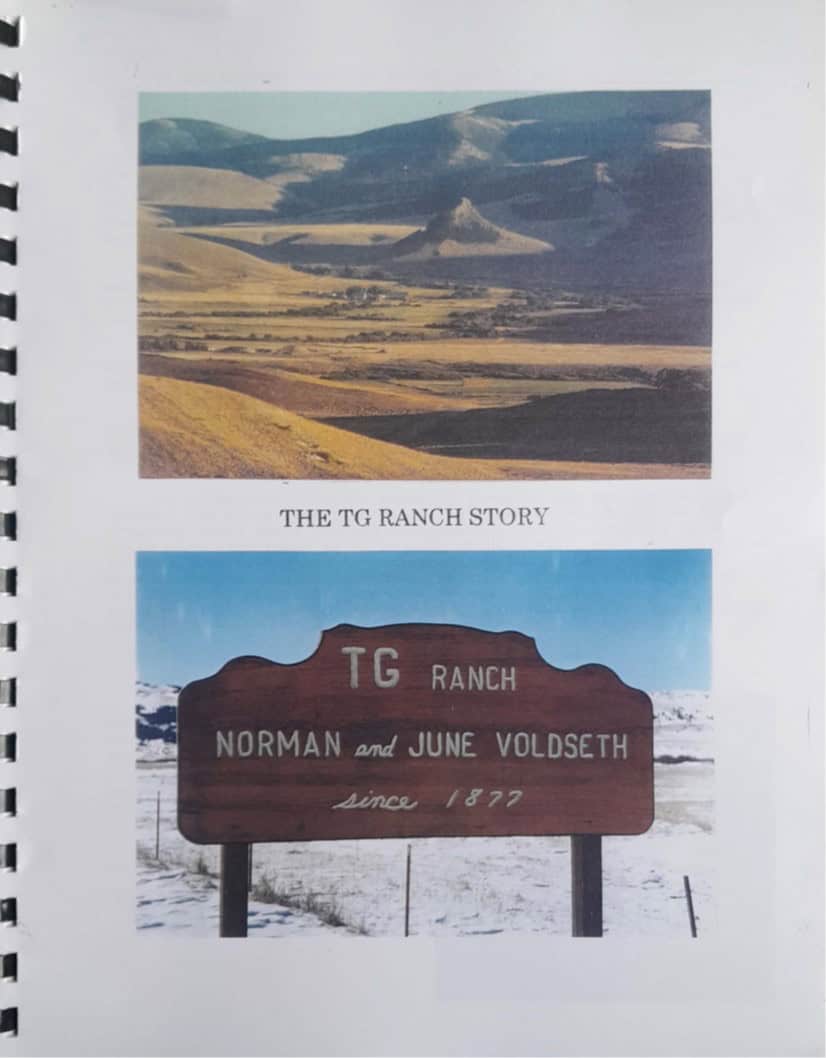

From Lennep: Photos (c) Inger Kari Nerheim. Copy of brand document courtesy of the owners, June and David Voldseth. Image of book on family history, see note 13.

Image of the brig Brødrene is credited to Sverresborg Trøndelag Folkemuseum, URL : https://digitaltmuseum.no/011025371421/bilde; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. See also the ship and vessel website Norway Heritage Hands across the Sea: http://www.norwayheritage.com/p_ship.asp?sh=nican

Notes

[1] Folketelling 1865 for 1722 Ytterøens prestegjeld, Digitalarkivet, f8651722_hefte.pdf, p. 100, 101.

[2] Aud Mikkelsen Tretvik, Pål Thonstad Sandvik, Anders Kirkhusmo og Ola Svein Stugu, Trøndelags historie, bind 3: Grenda blir global, 1850-2005, Trondheim 2005, pp. 136-138.

[3] Per Jevne, ed., Brevet hjem, En samling brev fra norske utvandrere, Adresseavisens forlag, Trondheim, 1975, pp. 23-25. The letter is written by Erland Blegen, in America Erland Taraldsen Tomasrud.

[4] Carlton C. Qualey, “A Typical Norwegian Settlement Spring Grove, Minnesota” , NAHA, volume IX, p. 54f.

[5] Charles Ellis, “History of Carbon, Wyoming’s First Mining Town.” Annals of Wyoming, volume 8, no. 4, April 1932, pp. 633-641; History of the Union Pacific Coal Mines, 1868 to 1940, The Colonial Press, Omaha, 1940.

[6] Montana, the Land and the People, Vol III, biography on Martin T. Grande, pp. 169-174.

[7] Roberta Carkeek Cheney, Names on the Face of Montana. The Story of Montana’s Place Names, Missoula, 1983. Fourth Printing 1990, p. 98.

[8] Harold Joseph Stearns, History of the upper Musselshell Valley to 1920, M.A. dissertation, University of Montana, 1966, p. 5.

[9] John Hailey was born August 29, 1835, in Smith County, Tennessee, and died in Boise, Idaho on April 10, 1921. In 1848 he had migrated with his family to Dade County, Missouri. In 1853 he crossed the plains west on a wagon train to Oregon and on August 7, 1856, he married Louisa M. Griffin in Jackson County, Oregon. They became parents of six children. The family moved to Washington Territory in 1862, but later moved to Boise, Idaho. Hailey became an active politician and was elected to the Forty-third Congress (March 4, 1873-March 3, 1875). He served as member of the Territorial council of Idaho in 1880. In 1884, Hailey was elected to the Forty-ninth Congress (March 4, 1885-March 3, 1887).

[10] “Subject: Smith Brothers Ranche”, March 19, 1941. From Research Worker Alva J. Vinton. Special Collections MSU 230.025.

[11] “First Sheep in Musselshell Valley Trailed Here in ‘77”, Meagher County Republican, November 18, 1926.

[12] “First Sheep..

[13] An important source on the Grande family is Norman M. Voldseth and June Voldseth, The TG Ranch Story, private publication, Lennep 1999. The book was given to Gunnar and Inger Kari Nerheim at a meeting in the Voldseth home early in September 2023.

Views: 108

Hi! Peter is my great great grandfather. This was a fun find. Thank you for the post!

Thank you! I am currently working on more articles on the emigration from the area around Trondheim. Feel free to write me at gunnar.nerheim@uis.no. Do you have any photo of Pete Jackson or from his life that you would enjoy us posting in the article? Full credits will be given, of course! Best regards, Gunnar