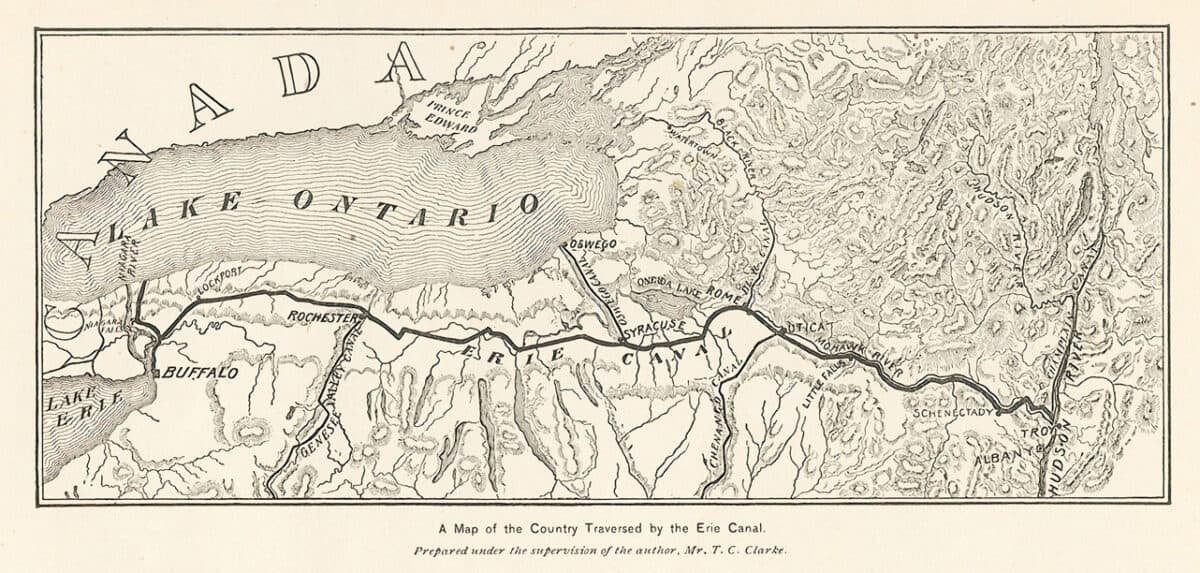

On October 21, 1825, most of the Norwegian emigrants from the sloop Restauration boarded a steamship from New York to Albany. From Albany they traveled west through the region of the brand-new canal, which was creating a direct route to Lake Erie from New York City. Only five days later, the whole length of the Erie Canal was officially opened, on October 26, 1825. Were they going to find their land of milk and honey?

New York governor DeWitt Clinton led the opening ceremonies. He traveled on the canal on board the Seneca Chief in the opposite direction, east from Buffalo to New York City, which meant that he met the Norwegian group on its way westward.[1]

The governor was one of the major proponents of the canal project, and the canal was an immediate success. The toll revenues quickly covered the construction costs of the canal. The Norwegian group disembarked at Holley, Orleans County, west of the city of Rochester, in early November.

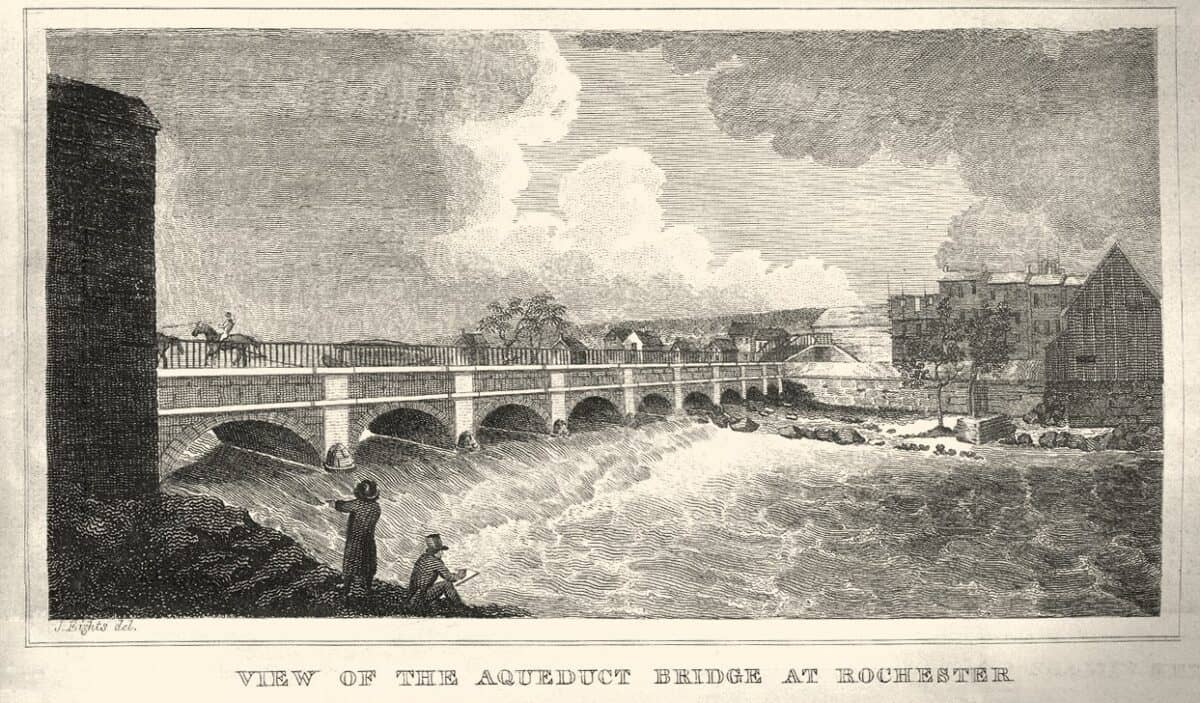

The aqueduct bridge at Rochester made it possible for canal boats on the Erie Canal to cross the Genesee River. The roaring Genesee River powering several mills and the calm Erie Canal run side-by-side at Rochester, before the canal makes a left turn to cross the river on the aqueduct. Image from the 1820’s; courtesy of the City of Rochester, NY.

Who was Joseph Fellows, the man who helped the Norwegian emigrants?

Over the years many historians have mentioned Joseph Fellows and his role in bringing the Norwegian immigrants from the port of New York to their new land in Murray, Orleans County. Cleng Peerson met Fellows the first time in the fall of 1824. He met an accomplished lawyer and a bachelor of his own age, who had been working together with rich and influential men since he was twenty years old.

Joseph Fellows Jr. emigrated with his family from Worcestershire, England, and arrived in New York in 1795. He was born in Redditch on July 2, 1782. Joseph was the eldest of five children, and Lydia, born during the Atlantic crossing from England to New York, was the youngest. After an extended stop in New York, the rest of the Fellows family traveled to Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, where they in time became involved in coal mining.

Thirteen-year-old Joseph Fellows Jr. remained in New York when the family continued. On June 24, 1796, his father had signed an apprenticeship contract for him with the lawyer Isaac Lewis Kip. Joseph Jr. was to live in Kip’s household and would receive instruction in the law. Upon completion of his apprenticeship, he would be qualified to become a lawyer. Kip was one of the descendants of a well-known Dutch family who had lived in Manhattan since Holland controlled the colony.[2]

Young Fellows did a good job for Pulteney

Joseph Fellows could hardly have been more fortunate with his apprenticeship. During his years of study with Kip, Fellows met many prominent men in American politics and business, including Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr. At Kip’s he also became acquainted with Colonel Robert Troup. When Joseph Fellows was admitted to the bar in 1803, Troup offered him the opportunity to work for him for an annual salary of six hundred dollars. Two years earlier, Troup had taken over as principal agent for Pulteney Estates.

Robert Troup did not regret his decision. In a letter to Joseph Fellows, dated Albany, November 10, 1810, he appointed Fellows as manager of the Geneva office. Troup expected Fellows to settle in Geneva as soon as possible. His annual salary was increased to $2,000 per year. A horse was at his disposal, and a new stone house was ready. Troup justified the promotion on the grounds that Fellows had performed his work loyally, with diligence and integrity over many years.

When Troup moved from Albany back to New York City in 1824, Fellows was given the responsibility for almost the entire area. In 1832, he became principal agent and director of Pulteney Estates, with an annual salary of $5,500.[3]

Fellows and the Norwegian emigrants

Besides his main work, Fellows was allowed to invest in his own projects. When he died, he was still a modest, unmarried man, but very wealthy. There is a widespread perception in the immigration literature, both the Norwegian and the American, that Joseph Fellows was a Quaker. This is patently false. According to a close relative, Fellows gave “generous support to the Episcopal Church.”

The role Fellows played in the first organized emigration to the United States from Norway was a small part of his total activities. Nevertheless, Fellows’ action on their behalf came to have major consequences for the Norwegian emigrants in their immediate future.[4] When most of the Norwegians in western New York chose to move westward some years later, Fellows again assisted them.

Land prices and conditions

According to long held and stubborn traditions in the Norwegian-American immigration literature, each adult in western New York received a tract of forty acres of land and paid five dollars an acre for the land. However, the Pulteney Estates offered the Norwegian immigrants the same sales conditions as other buyers got. They bought their land on credit, and had to pay off all their debts to the Pulteney Estates year by year before they would get title to their land.

The land was “sold to the Norwegians by Joseph Fellows at five dollars an acre,” Rasmus B. Anderson maintained, “but as they had no money to pay for it, Mr. Fellows agreed to let them redeem it in ten annual instalments.”[5] The original source for the information was Ole Rynning in 1837.[6] Almost all later writers accepted Rynning’s account uncritically, observed Richard Canuteson in 1954.[7]

Purchases by Cleng Peerson before the emigrants arrived

During his research in the Pulteney Papers, Canuteson discovered a map which showed that Cleng Peerson was the owner, “presumptively at least, of four tracts, alone or in partnership with someone else: Lot 15, at the mouth of the creek, 78.52 acres; jointly with Nelson (probably either Nels or Cornelius Nelson Hersdal), the east part of Lot 25, approximately two thirds of the 154.89 acres; the south part of Lot 26, possibly three fifths of the 170.44 acres; and the western part, about two thirds, of Lot 27, 153.70 acres.”

The immigrants Stangeland and Rossadal shared Lot 37 (97.50 acres) and Hervig and Neilson shared Lot 49 (90.46 acres). George Johnson and Knut Evenson, who arrived in Kendall in 1831, shared Lot 62 (99.61 acres). Another lot to the south of this one, (96.74 acres) was simply marked “Norwegians”. Very few among the Norwegian immigrants were able to pay even small amounts on their land between 1825 and 1833.[8]

The land was located in a swampy and forested area

The new homesteads were located in a swampy, forested area where the water in many places was four feet deep. “The land was thickly overgrown with woods and difficult to clear,” according to Ole Rynning. “Consequently, during the first four or five years, conditions were very hard for these people. They often suffered great need and wished themselves back in Norway.”[9] The group who had emigrated on the Restauration came from the coastal region of Rogaland County, with hardly any large forests. Few people had any major experience in handling lumber, and fisheries were a mainstay, not least when other food was scarce.

Earlier American settlers in the Kendall area had had to deal with the same problems. Even though many came from the mountains of Vermont, they had to adapt to a change of climate, air temperature, food and occupation. The dense forest in the area had to be cleared before the soil could be cultivated. They also had to learn to live with malaria, which thrived in the humidity of the forest floor, as soon as the summer heat arrived.

Illness and death the first years

The Norwegians came too late in the year to grow their own food, and had to buy from others during the first winter. However, most of them did not have any cash. Many among them experienced extended periods of illness, especially due to ague or malaria. Some of them died these first years. Tormod Jensen Madland died in 1826 and his wife Siri in 1829. Aanen Thoresen Brastad (Oyen Thompson) and his youngest daughter Birthe Karine also died in 1826, over in Rochester. Cornelius Nelson Hersdal, the brother-in-law of Cleng Peerson, died in 1833. His widow Kari Pedersdatter was left with seven children aged from a few months to twenty years. Sven Jacobsen Aasen (Swaim Jacobson), who emigrated from Tysvær in 1829, together with his wife Johanna Johnsdatter Hervig and three children, died in 1831.[10]

The first year was critical for all new homesteaders

The first year was always critical for new homesteaders, wherever they came from. Their American neighbors knew from experience how important it was that pioneers brought with them tools and corn seed. Building a shelter for the family had priority, followed by a log cabin. “Both the lean-to and cabin would be built from materials at hand, and often simultaneously with the clearing of land.” The planting of the first crop of corn was crucial. When the settlement was on wooded land, a suitable site would have to be cleared. “Whatever the location and circumstances, corn was the universal crop on the trans-Appalachian frontier. It needed little cultivation.”[11]

Most of the Norwegian immigrants had never seen or eaten corn. For more than a hundred years, generations of settlers had learned that “Without this gift of the Indian, so easy to plant and so adaptable to frontier conditions, so nourishing and with so many uses, the cycle of life and labor on the early frontier would have been different. From the time of his arrival, the main effort of the early settler was directed to the cultivation of the corn crop”.

The Norwegian immigrants settled in a dynamic economic region, but very few among them tried to get employment outside their own circle. Some of them had skills needed outside agriculture and got employment. However, they had considerable language problems. Most of them did not speak English, and they tended to seek security by clustering together in their own misery.[12]

The search for better land

The first Norwegians in western New York worked hard for several seasons to grow enough food for their families to last through the long and cold winters. In their letters home to Norway they were unable to hide their disappointment with their new life in the woods. Very few Norwegians followed in their footsteps. The first Norwegian colony in western New York was not a Canaan’s Land, the Promised Land from the Bible, where food was plentiful and the rivers flowed with milk and honey. The first six Norwegian families moved from New York State to La Salle County, Illinois, in 1834. Their move marked the beginning of the second Norwegian settlement in the United States, known as the ‘Fox River Settlement’.

Credits

“Opening of the Erie Canal, in 1825” / [drawing by] A.R.W. ; engraved by] Swinton So. — From an unidentified history text, p. 167 ; approximately 1890? Image and maps from the Erie Canal Website, Copyright © 2000-2022 by Frank E. Sadowski Jr. Downloaded from https://www.eriecanal.org/general-1.html Jan 30, 2025.

“View of the Aqueduct bridge at Rochester”, by James Eights, 1824. From “A Geological and Agricultural Survey of the District Adjoining the Erie Canal in the State of New York” by Stephen Rensselaer (Printed by Packard & Van Benthuysen, 1824) Images courtesy of the Department of Rare Books & Special Collections, University of Rochester Library. https://www.clengpeerson.no/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/View-of-Aqueduct-bridge-at-Rochester-1820s-.jpg

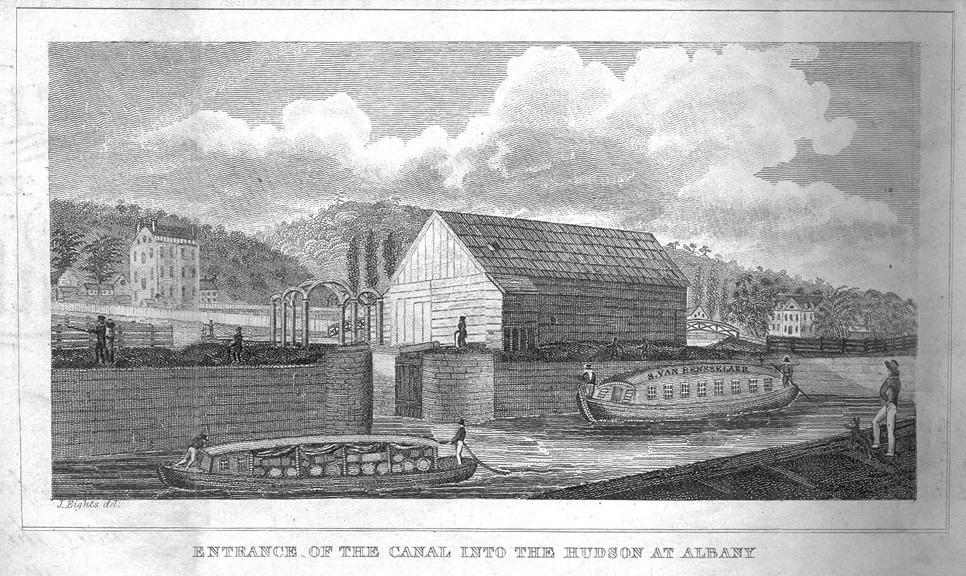

“Entrance of the Canal into The Hudson at Albany, 1823” by James Eights. — From: Annual Report of the State Engineer and Surveyor of the State of New York for the fiscal year ended September 30, 1915 (Albany : J. B. Lyon Co, printers, 1916), facing p. 10. https://eriecanal.org/east-2.html#Albany

Map of the Erie Canal and Lake Ontario. From Water-ways from the Ocean to the Lakes / by Thomas Curtis Clarke — Scribners Magazine, Vol. XIX, no. 15, 1896, p. 104. Downloaded from https://eriecanal.org/maps.html

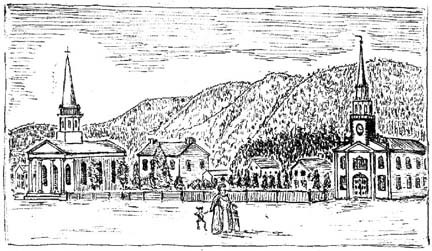

Image from Geneva in the Pulteney Papers. Source: James D. Folt in Crooked Lake Review, Fall 2003: The “Alien Proprietership” . The Pulteney Estate during

the Nineteenth Century. http://www.crookedlakereview.com/articles/101_135/129fall2003/129folts.html

Notes

[1] Ronald E. Shaw, Erie Water West. A History of the Erie Canal 1792-1854, Lexington, KY 1966.

[2] Gunnar Nerheim, Norsemen Deep in the Heart of Texas. Norwegian Immigrants 1845 – 1900, Texas A&M Press, College Station, TX, 2024, p. 65.

[3] Richard Canuteson, «A Little Light», pp. 90-91.

[4] Nerheim, Norsemen Deep in the Heart, pp. 62-63.

[5] Anderson, The First Chapter of Norwegian Immigration, 1895, p. 77.

[6] Ole Rynning, Sandfærdig Beretning om Amerika til Oplysning og Nytte for Bonde og Menigmand. Forfattet af En norsk, som kom derover i Juni Maaned 1837, Christiania 1839, p. 6.

[7] Richard Canuteson, “A Little More Light on the Kendall Colony”, p. 90.

[8] Richard Canuteson, “A Little More Light on the Kendall Colony”, p. 93; M. Joette Knapp, Town Historian, “A Brief History of Kendall” https://orleans.nygenweb.net/tandv/kendall.html

[9] Blegen, “Ole Rynning’s True Account of America,” p. 73.

[10] Gunleif Seldal, “The Sloopers,” p. 32.

[11] Malcolm J. Rohrbough, The Trans-Appalachian Frontier. People, Societies and Institutions 1775-1850 (New York: Oxford University Press), 1978, pp. 33-34.

[12] Henry J. Cadbury, “The Norwegian Quakers of 1825,” The Harvard Theological Review, 18, no. 4 (October 1925): pp. 293-319; Anderson, The First Chapter of Norwegian Immigration, 1895, p. 185.

Views: 70