The Red River Colony was the first white settlement in the Lake Winnipeg region. It was established by Lord Selkirk in 1811 and became an important center for fur trapping.[1] The first man killed at the Seven Oaks Massacre on June 19, 1816, was the Norwegian “Lieuenant” Holte. He was the leader of a small band of Norwegians who arrived at the settlement York Factory in September 1814. A member of Holte’s group, Peter Dahl, was the first Norwegian farmer in the Red River Valley.[2]

Ox carts in the Red River Colony

The ox cart routes operating from the Red River Colony to St. Paul, Minnesota, and other places between 1820 and 1870 are well known even today. Trade conducted along the Red River trails played an important role in the early settlement of Minnesota and North Dakota in the United States, and it marked the beginning of settlements in western Canada.

The large, two-wheeled ox cart was made entirely of wood. Originally, small horses were used to draw the carts. But after cattle became common in the Selkirk Settlement in the 1820s, oxen became the preferred animal. Oxen had greater endurance, and their cloven hooves did better than horses in swampy areas. The wood axles were seldom greased. The sound of a train of carts sounded like an untuned violin. It could be heard for miles before anyone could see the carts.

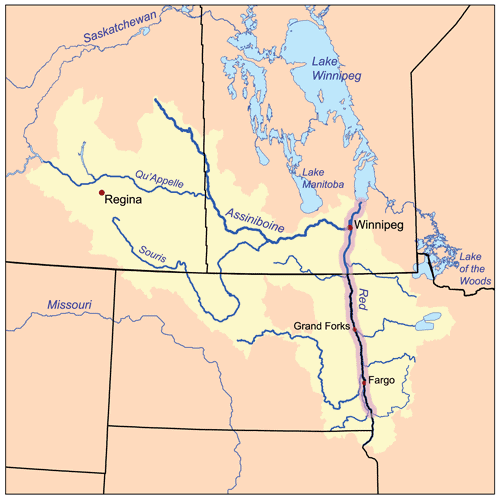

Ox carts passed from one river crossing to the next, over the flat prairie, through swamps and woodlands. They stopped at trading posts, missionary establishments, inns, villages, and towns along the way.[3] The Red River trails extended from the Red River Colony via fur-trading posts such as Pembina and St. Joseph in the Red River Valley to Mendota and St. Paul, Minnesota. Furs were the main cargo on the trip to St. Paul, while trade goods and supplies were carried on the return trip to the Red River Colony.

The heyday of the Red River ox cart trade occurred between 1840 and 1870. They were superseded by steamboats and railways. Free traders, independent of the Hudson’s Bay Company and outside its jurisdiction, dominated the ox cart trade, and St. Paul became an important trading center. “Though crudely made and noisy because of the wheel schreeching on the wood axles”, wrote Elwyn B. Robinson, “the carts provided effective transportation. They and the level, treeless plain made it possible to carry freight to St. Paul and Mendota for a fraction of the cost of transporting an equivalent amount by water to Hudson’s Bay.”[4] Some of the first Scandinavians who explored the possibilities for settling in western Canada in the 1870s, traveled along these trails.

Steamboats on the Red River

After the steamboats were introduced on the Red River and the bigger lakes travel became easier and cheaper.[5] The Anson Northup was the first steamboat on the Red River. On its first trip between Breckenridge, Minnesota and Fort Garry, the steamboat left Breckenridge on June 6, 1859, and reached Fort Garry on June 10. The return trip upstream to Fort Abercrombie took eight days. The trip was an experiment and it proved that regular steamboat traffic would be feasible. The following years larger steamboats were introduced. Low water, lack of freight, the Civil War, and unfriendly Indians, however, all combined to slow down the development of the steamboat traffic on the Red River in the 1860s.

Steamboats got their breakthrough in the 1870s. The Selkirk, owned by Hill, Griggs & Company of St. Paul, was built at McCauleyville and launched in 1871. It had a tonnage of 108. Since the bottom was flat, the boat could move at a water depth as low as 18 inches. In the winter of 1871/1872, all steamboats on the river came under the control of Norman W. Kittson, St. Paul. He built the steamboat Dakota at Breckenridge in 1872, followed by the side-wheeler, Cheyenne, built at Grand Forks in the winter of 1873/74. During the 1873 season there was considerable steamboat traffic on the Red River.

The steamboat trip to Winnipeg, Manitoba, was shortened somewhat when the Northern Pacific Railway began running through Moorhead, Minnesota. In fall 1872 a branch of the St. Paul & Pacific Railroad reached the Red Lake River at Crookston, and replaced Moorhead as the main transshipment point on the Red River. A railway spur from Crookston to Fisher’s Landing was completed in 1875.[6] This became the new shipping point for cargo and passengers on the Red River.

A growing trade in Winnipeg

The trade volume between St. Paul, Minnesota, and Winnipeg, Manitoba, increased during the 1870s. City boosters incorporated Winnipeg as a city on November 8, 1873. Winnipeg was “established by businessmen, for business purposes, and businessmen were its first and natural leaders,” wrote Alan F. J. Artibise.[7] The city leaders worked hard to make sure the planned transcontinental railway would pass through Winnipeg. It took time and much lobbying before that decision was finally made. Meanwhile Winnipeg experienced a strong economic boom in connection with the building of the Pembina railway line.

The construction of the Pembina railway

Construction of the Pembina Railway began in 1874 and the last spike on the line was driven on December 3, 1878. The line began at St. Boniface, south of Winnipeg, and ended at Emerson, close to the United States border. It was connected to a United States railroad terminus at St. Vincent, Minnesota. Finally Winnipeg had got “an effective outlet for the wheat crops of its surrounding hinterland and good times once more seemed in store for the young community.”[8] The completion of the Pembina line meant that there was now a continuous rail link between Winnipeg, Minneapolis/St. Paul, and Chicago, and also other points in the American Mid-West. The Pembina railway established a continuous rail link between Winnipeg and Eastern Canada via the United States.

An important transport route for settlers

The Pembina railway became an important transport route for settlers and investors along the Red River Valley north to Winnipeg. The railway triggered the first economic boom in Winnipeg. In 1881 Winnipeg had 7,985 inhabitants. When the Canadian Pacific Railroad building boom ended in 1883, many businesses declined, and some went bust. Economic growth in Winnipeg experienced a rebound in the late 1880s. The Canadian census of 1886 showed that Winnipeg had nine times as many people as the next largest urban center in western Canada and had more inhabitants than all of Saskatchewan. The Canadian Pacific Railroad made Winnipeg the distribution and administration center of the agricultural lands west of the city. The Manitoba population increased from 25,000 in 1871 to 62,000 in 1881 and 153,000 in 1891.

Winnipeg became the main city for Scandinavians in Canada in the 1880s

In 1881 over 67 per cent of inhabitants in Winnipeg had been born in Canada, while 32 per cent were foreign born. The 1881 census counted only 32 Scandinavians and Icelanders. Ten years later the number of Scandinavians had increased to 1,193 and in 1901 to 2,199. People coming from Great Britain still constituted the largest group of foreign-born in Winnipeg in 1891, but the Scandinavians were the largest non-English- speaking group and accounted for 5 per cent of the foreign born.

“Prior to the First World War,” Artibise writes, “Winnipeg was still receiving large number of migrants and a man’s birthplace, ethnic origin, and religion told a good deal about his position in society.”[9] Two- and four-story brick structures lined the streets of the Winnipeg business district by the late 1880s. The financial and wholesale district got more and more paved streets and gas lighting. Water was obtained from the Assiniboine River, but distribution was still a problem since the few water mains only served a limited part of the city. People living in many streets and neighborhoods still had to buy water by the barrel. The sewage system was inadequate, and cesspools were common.

Most of the Scandinavians without education and English skills had to accept low paid manual jobs, but later became more involved in different kind of small businesses. Scandinavian servant girls were regarded as hard and dependable workers and were much sought after in Winnipeg. A Scandinavian congregation was organized in Winnipeg in 1885. A frame church with a capacity to seat 250 persons was built in 1886.

There was a strong and dynamic Swedish group in Winnipeg until World War II. Since almost everyone travelling to the Canadian prairies had to pass through Winnipeg, it became a center of immigrant activity. Much of the population was transient. Many Norwegians and Danes also lived in Winnipeg, but the Swedes dominated with their churches, businesses, hotels, boarding houses, and cafés.[10] In 1911, more than 1,400 people of Swedish birth were on record as living in the city. After World War I, the number of Swedes in Winnipeg declined.[11]

Image credits:

Map Red River of the North. Created by Carl Musser, based on USGS and Digital Chart of the World. Licenced under Wikimedia Commons, The Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike 2.5 generic licence. Wikimedia (2023) Available at:https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/66/Redrivernorthmap.png (accessed 06 June 2023).

[1] Elwyn B. Robinson, History of North Dakota, Lincoln, Nebraska, 1966. p. 62-72.

[2] Paul Knaplund, “Norwegians in the Selkirk Settlement 1815-1870”, NAHA, volume VI, 1931.

[3] Rhoda B. Gilman, Carolyn Gilman and Deborah M. Stultz, The Red River Trails, Oxcart Routes Between St. Paul and the Selkirk Settlement, 1820-1870, St. Paul, Minnesota 1979; Harry Baker Brehaut, P. Eng, “The Red River Cart and Trails: The Fur Trade”, MHS Transactions, Series 3, Number 28, 1971-72 season; William G. Fonseca, ”On the St. Paul Trail in the Sixties”, MHS Transactions, Series 1, No. 56, Read 25 January 1900; Hartwell Bowsfield, “The United States and Red River Settlement”, MHS Transactions, Series 3, Number 23, 1966-67 season.

[4] Elwyn B. Robinson, History of North Dakota, Lincoln, Nebraska, 1966. p. 78.

[5] Molly McFadden, “Steamboating on the Red”, MHS Transactions, Series 3, 1950-51 season; Elwyn B. Robinson, History of North Dakota, Lincoln, Nebraska, 1966. p. 114-116; Alan F. J. Artibise, Winnipeg: A Social History of Urban Growth, 1874-1914, Montreal 1975, p. 78f.

[6] Elwyn B. Robinson, History of North Dakota, pp.120-122.

[7] Alan F. J. Artibise, Winnipeg: A Social History of Urban Growth, 1874-1914, p. 25.

[8] Alan F. J. Artibise, Winnipeg: A Social History of Urban Growth, 1874-1914, p. 68.

[9] Alan F. J. Artibise, Winnipeg: A Social History of Urban Growth, 1874-1914, p. 139.

[10] Lars Ljungmark, “Swedes in Winnipeg up to the 1940’s: Inter-Ethnic Relations,” in Dag Blanck and Harald Runblom, eds., Swedish Life in American Cities, Uppsala: Centre for Multiethnic Research, 1991; Lars Ljungmark, Svenskarna i Winnipeg. Porten til prærien 1872-1940, Växjø 1994.

[11] Lars Ljungmark, “Swedes in Winnipeg up to the 1940’s: Inter-Ethnic Relations,” in Dag Blanck and Harald Runblom, eds., Swedish Life in American Cities; Lars Ljungmark, Svenskarna i Winnipeg. Porten til prærien 1872-1940, Växjø 1994.

Views: 523